颈椎后纵韧带骨化症(OPLL)可产生对脊髓、神经根的压迫,并出现相应的神经功能障碍。其病理基础是后纵韧带的成纤维细胞出现骨向分化,并在患者的后纵韧带组织内出现异位骨化。牵张应力刺激可使后纵韧带成纤维细胞表现出一定的成骨细胞活性,被认为是促进颈椎OPLL进展的重要因素,但其机制尚不明了[1-4]。转化生长因子β1(TGF-β1)可增加成纤维细胞的胶原合成,促进细胞外基质沉积,而这也正是成纤维细胞出现骨向分化进程中的表现[5-7]。因此,推测牵张应力刺激可能对后纵韧带细胞中的TGF-β1表达有所影响,并借此促进其骨化。本研究通过对体外培养的颈椎OPLL患者的后纵韧带成纤维细胞加载牵张应力刺激,观察其骨化指标和TGF-β1基因的表达变化,研究TGF-β1在该进程中的作用,从而证实以上推论。

1 材料与方法 1.1 材料和设备收集本院12例接受颈前路手术的颈椎OPLL患者的后纵韧带组织,其中男7例,女5例;平均年龄52.1(38~62)岁。实验所用主要试剂及设备如下。DMEM高糖培养基(Gibco公司,中国),TRIzol细胞RNA抽提用裂解液、大容量cDNA反转录试剂盒(Life Technologies公司,美国),SYBR Primix Ex Taq Ⅱ PCR试剂盒(TaKaRa公司,日本),总RNA提取试剂盒(天根生化科技有限公司,北京),外源性TGF-β1(Humanzyme公司,美国),TGF-β1抗体、IgG(Epitomics公司,美国),ABI 7500 RT-PCR扩增仪、ABI 2720 cDNA反转录仪(Life Technologies公司,美国),核酸蛋白测定仪(Eppendorf公司,美国),细胞牵张应力加载仪(Flexercell公司,美国)。

1.2 细胞培养及鉴定将所取标本剪成小于0.5 cm×1.0 cm×1.0 cm的小块组织,将其均匀铺洒于50 mL细胞培养瓶中,静置于细胞培养箱内,采用组织块培养法进行体外培养。待组织块周围细胞爬出后,每3~5 d更换一次培养液,待细胞铺满瓶底约80%后,加入0.5~1.0 mL 0.25%胰酶-EDTA液进行消化传代。取第3代细胞用于实验。将细胞接种在培养板内的盖玻片上,置入培养箱内过夜,待细胞贴壁。次日对细胞进行HE及免疫荧光染色鉴定,荧光倒置相差显微镜下观察其形态学特点。

1.3 分组及对照设计按照3×105/孔的密度将细胞接种在特制的Flexercell培养板内。取2块培养板分别加载牵张应力刺激12 h及24 h,并分别设静置相同时间的对照组。另取2块培养板接种细胞,并在其中一块的培养孔中分别依次加入浓度为0、0.1、1.0、10.0 ng/mL的外源性TGF-β1(浓度为0视为对照组),静置24 h;在另一块培养板的培养孔中接种细胞并加入浓度为2.0 μg/mL的TGF-β1抗体,并设空白对照组,同时选择对TGF-β1表达没有影响但结构相似的IgG以相同浓度设为参照组,各组均加载牵张应力刺激24 h。所有实验重复2次。

1.4 牵张应力加载确保培养板底部硅胶膜处于水平位置后,将其放入培养箱过夜待细胞贴壁。次日在电子显微镜下确认细胞的贴壁及生长状态良好后,更换培养液同步化24 h,以确保细胞的生长状态一致。同步化完成后将培养板再次放入培养箱,开启计算机控制中心,连接负压抽吸泵,设置牵张应力参数,幅度10%、频率0.5 Hz,作用时间为12 h及24 h。

1.5 骨化指标和TGF-β1的检测按上述分组,采用TRIzol法收集各培养孔中细胞的总RNA,通过核酸蛋白光谱仪测定其纯度和浓度。设计合成RNA引物,引物序列见表 1。使用大容量cDNA反转录试剂盒对提取的RNA进行反转录,随后进行荧光实时定量PCR,选择相对定量分析法进行分析,以β-actin作为内标基因,研究相关基因的相对表达差异。

|

|

表 1 PCR引物序列 Table 1 Primer sequences |

应用SPSS 18.0软件对数据进行统计学分析,数据以x±s表示,两组间的比较采用Student t检验,多组间比较采用方差分析,多组间的两两比较采用Dunnet t检验或Bonferroni检验。以P < 0.05为差异有统计学意义。

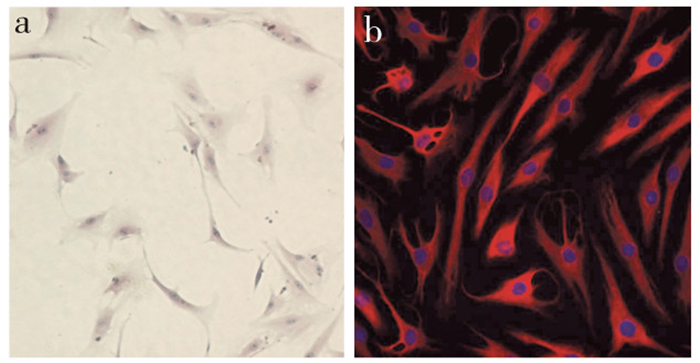

2 结果 2.1 后纵韧带细胞的HE及免疫荧光染色鉴定经HE及免疫荧光染色后,在倒置相差显微镜下观察,来源于颈椎OPLL患者的后纵韧带成纤维细胞呈梭形、纺锤形及多角的星形,细胞核大、卵圆形,部分细胞处于有丝分裂期。细胞核经DAPI染为蓝色,细胞质波形蛋白经TRITC标记后呈红色阳性表达,可证实其为成纤维细胞(图 1)。

|

a:HE染色(×40) b:免疫荧光染色(×40) a:HE staining(×40) b:Immunofluorescence staining(×40) 图 1 后纵韧带成纤维细胞 Figure 1 Posterior longitudinal ligament fibroblasts |

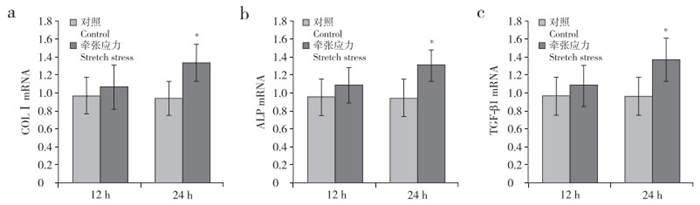

来源于颈椎OPLL患者的后纵韧带成纤维细胞经牵张应力刺激12 h及24 h后,细胞中COLⅠ、ALP和TGF-β1的mRNA表达与静置相同时间的对照组相比均有所升高,在24 h时其差异具有统计学意义(P < 0.05,图 2)。

|

a:COLⅠ b:ALP c:TGF-β1;*与对照组相比,P < 0.05 a:COLⅠ b:ALP c:TGF-β1;* P < 0.05, compared with control group 图 2 牵张应力刺激12 h及24 h后COLⅠ、ALP和TGF-β1的mRNA表达 Figure 2 mRNA expression of COLⅠ, ALP and TGF-β1 after 12 h and 24 h stress stimulation |

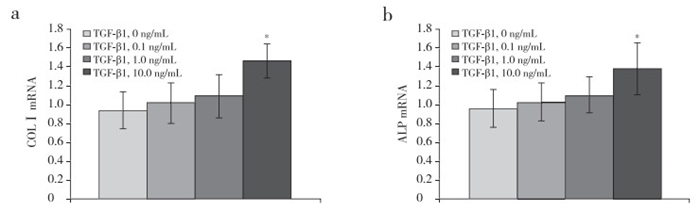

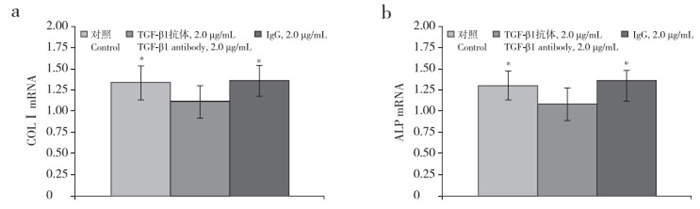

在接种后纵韧带细胞的培养孔中加入浓度分别为0、0.1、1.0、10.0 ng/mL的外源性TGF-β1,静置24 h后,细胞中COLⅠ及ALP的mRNA表达量升高,其中10.0 ng/mL浓度组与0 ng/mL组相比差异具有统计学意义(P < 0.05,图 3)。而经牵张应力刺激24 h后,对照组及IgG组细胞中COLⅠ及ALP的mRNA表达量升高幅度均明显大于TGF-β1组,差异有统计学意义(P < 0.05,图 4)。

|

a:COLⅠ b:ALP;*与TGF-β1 0 ng/mL组相比,P < 0.05 a:COLⅠ b:ALP; * P < 0.05, compared with TGF-β1 0 ng/mL group 图 3 TGF-β1作用24 h后COLⅠ和ALP的mRNA表达 Figure 3 mRNA expressions of COLⅠand ALP after stimulation with TGF-β1 for 24 h |

|

a:COLⅠ b:ALP;*与TGF-β1抗体2.0 μg/mL组相比,P < 0.05 a:COLⅠ b:ALP; * P < 0.05, compared with TGF-β1 antibody 2.0 μg/mL group 图 4 TGF-β1抗体作用并机械应力刺激24 h后COLⅠ和ALP的mRNA表达 Figure 4 mRNA expressions of COLⅠand ALP after 2 μg/mL TGF-β1 antibody plus 24 h stress stimulation |

OPLL的发生和发展被认为与牵张应力刺激关系密切。日本学者在分析了颈椎的活动度与骨化进展快慢之间的关系后认为,颈椎活动度较小的患者骨化进展的速度相对较慢,反之则较快[8-9]。也有学者研究证实,在颈椎OPLL患者中,颈椎活动度越大的节段韧带骨化的程度往往越严重[10-11]。在临床随访中,也发现接受颈椎后路椎板切除或椎管成形术等后路术式的患者由于颈椎后方结构被破坏,可能产生颈椎不稳而导致后纵韧带的骨化灶进展加速;而接受前路融合术的患者,因为融合后去除了颈椎节段间的不稳因素,其后纵韧带的骨化灶进展明显减慢,甚至完全消失[12-14]。因此,牵张应力刺激被认为是促进颈椎OPLL进展的重要因素。

由于OPLL起病过程缓慢,病因复杂,致病因素多,尚没有建立理想的活体动物模型,多采用动物或者人体的后纵韧带组织进行体外研究。本研究通过颈前路手术获取颈椎OPLL患者的后纵韧带标本,并采取组织块培养法进行细胞体外培养。对培养成功的细胞加载机械牵张应力刺激的原理是利用真空泵抽吸特制的细胞培养板底部硅胶模,形成负压,使细胞受到机械牵张,模拟体内后纵韧带承受的机械应力刺激。针对人颈椎活动的特点,本研究将牵张应力刺激的参数设置在低频率、低幅度状态,以更符合生理状态,而且也避免了过高频率或过高幅度对体外培养的韧带细胞可能造成的损伤。

选择合适的成骨化指标是观察牵张应力刺激对成纤维细胞骨化进程的影响,并进一步深入研究颈椎OPLL发生、发展过程的前提。COLⅠ是不溶性纤维型蛋白质,属于一类细胞外基质,COLⅠ含量的增加会使韧带纤维化的程度增高,其分泌增多是骨基质形成的特征性表现[15]。ALP通过水解有机磷酸酯能为羟基磷灰石沉积提供必需的磷酸基团,利于细胞骨化,是骨形成过程中矿化阶段的极好标志物,定量ALP可作为成骨活性的可靠指标[16]。因此本研究选择了COLⅠ和ALP作为观察成纤维细胞骨化进程的特异性指标。实验结果证实牵张应力刺激可促进颈椎OPLL患者后纵韧带成纤维细胞的成骨化指标升高,加速其骨向分化,同时亦发现在该进程中TGF-β1的表达有明显上调。TGF-β1与颈椎OPLL关系密切,可增加成纤维细胞胶原蛋白合成,促进细胞外基质沉积。Li等[17]通过实验发现高浓度葡萄糖可促进大鼠后纵韧带细胞分泌TGF-β1,并使胶原蛋白表达升高,促进骨化,而采用抗体中和TGF-β1作用后,高浓度葡萄糖对大鼠后纵韧带细胞骨化的促进作用减弱,从而证实TGF-β1在高糖促进OPLL进程中的作用。在本实验中,加入外源性的TGF-β1作用后,颈椎OPLL患者的后纵韧带成纤维细胞即使在无应力刺激时其骨化指标表达亦明显升高,且呈现出一定的浓度依赖作用;同时,在加入TGF-β1抗体中和其作用后,应力刺激对后纵韧带成纤维细胞骨化指标表达的促进作用明显减弱。因此可认为TGF-β1在外界的牵张应力刺激传导至后纵韧带成纤维细胞内并促进其骨向分化的过程中具有重要作用。

本研究克服了以往颈椎OPLL患者的后纵韧带标本为退变的病理组织、生长分化能力弱、体外培养成活率低的困难,采用组织块培养法成功培养了颈椎OPLL患者的后纵韧带成纤维细胞。证实了TGF-β1在牵张应力刺激促进颈椎OPLL患者后纵韧带成纤维细胞骨向分化进程中的作用。

| [1] | Chang H, Song KJ, Kim HY, et al. Factors related to the development of myelopathy in patients with cervical ossification of the posterior longitudinal ligament[J]. J Bone Joint Surg Br, 2012, 94(7): 946–949. |

| [2] | Liu X, Kumagai G, Wada K, et al. Suppression of osteogenic differentiation in mesenchymal stem cells from patients with ossification of the posterior longitudinal ligament by a histamine-2-receptor antagonist[J]. Eur J Pharmacol, 2017, 810: 156–162. DOI:10.1016/j.ejphar.2017.07.013 |

| [3] | Liu X, Kumagai G, Wada K, et al. High osteogenic potential of adipose-and muscle-derived mesenchymal stem cells in spinal-ossification model mice[J]. Spine (Phila Pa 1976), 2017. [Epub ahead of print] |

| [4] | Li H, Jiang LS, Dai LY. A review of prognostic factors for surgical outcome of ossification of the posterior longitudinal ligament of cervical spine[J]. Eur Spine J, 2008, 17(10): 1277–1288. DOI:10.1007/s00586-008-0740-8 |

| [5] | Dang PN, Herberg S, Varghai D, et al. Endochondral ossification in critical-sized bone defects via readily implantable scaffold-free stem cell constructs[J]. Stem Cells Transl Med, 2017, 6(7): 1644–1659. DOI:10.1002/sct3.2017.6.issue-7 |

| [6] | Bahney CS, Jacobs L, Tamai R, et al. Promoting endochondral bone repair using human osteoarthritic articular chondrocytes[J]. Tissue Eng Part A, 2016, 22(5/6): 427–435. |

| [7] | Dang PN, Dwivedi N, Phillips LM, et al. Controlled dual growth factor delivery from microparticles incorporated within human bone marrow-derived mesenchymal stem cell aggregates for enhanced bone tissue engineering via endochondral ossification[J]. Stem Cells Transl Med, 2016, 5(2): 206–217. DOI:10.5966/sctm.2015-0115 |

| [8] | Agrawal D, Sharma BS, Gupta A, et al. Efficacy and results of expansive laminoplasty in patients with severe cervical myelopathy due to cervical canal stenosis[J]. Neurol India, 2004, 52(1): 54–58. |

| [9] | Cho WS, Chung CK, Jahng TA, et al. Post-laminectomy kyphosis in patients with cervical ossification of the posterior longitudinal ligament:does it cause neurological deterioration?[J]. J Korean Neurosurg Soc, 2008, 43(6): 259–264. DOI:10.3340/jkns.2008.43.6.259 |

| [10] | Fujimura Y, Nishi Y, Chiba K, et al. Multiple regression analysis of the factors influencing the results of expansive open-door laminoplasty for cervical myelopathy due to ossification of the posterior longitudinal ligament[J]. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg, 1998, 117(8): 471–274. DOI:10.1007/s004020050296 |

| [11] | Hou Y, Liang L, Shi GD, et al. Comparing effects of cervical anterior approach and laminoplasty in surgical management of cervical ossification of posterior longitudinal ligament by a prospective nonrandomized controlled study[J]. Orthop Traumatol Surg Res, 2017, 103(5): 733–740. DOI:10.1016/j.otsr.2017.05.011 |

| [12] | Chen Y, Chen D, Wang X, et al. Anterior corpectomy and fusion for severe ossification of posterior longitudinal ligament in the cervical spine[J]. Int Orthop, 2009, 33(2): 477–482. DOI:10.1007/s00264-008-0542-y |

| [13] | Wang S, Xiang Y, Wang X, et al. Anterior corpectomy comparing to posterior decompression surgery for the treatment of multi-level ossification of posterior longitudinal ligament:a meta-analysis[J]. Int J Surg, 2017, 40: 91–96. DOI:10.1016/j.ijsu.2017.02.058 |

| [14] | Chen Y, Guo Y, Chen D, et al. Long-term outcome of laminectomy and instrumented fusion for cervical ossification of the posterior longitudinal ligament[J]. Int Orthop, 2009, 33(4): 1075–1080. DOI:10.1007/s00264-008-0609-9 |

| [15] | Pavlin D, Dove SB, Zadro R, et al. Mechanical loading stimulates differentiation of periodontal osteoblasts in a mouse osteoinduction model:effect on typeⅠcollagen and alkaline phosphatase genes[J]. Calcif Tissue Int, 2000, 67(2): 163–172. DOI:10.1007/s00223001105 |

| [16] | Wennberg C, Hessle L, Lundberg P, et al. Functional characterization of osteoblasts and osteoclasts from alkaline phosphatase knockout mice[J]. J Bone Miner Res, 2000, 15(10): 1879–1888. DOI:10.1359/jbmr.2000.15.10.1879 |

| [17] | Li H, Liu D, Zhao CQ, et al. High glucose promotes collagen synthesis by cultured cells from rat cervical posterior longitudinal ligament via transforming growth factor-beta1[J]. Eur Spine J, 2008, 17(6): 873–881. DOI:10.1007/s00586-008-0662-5 |

2018, Vol.16

2018, Vol.16  Issue(1): 41-45

Issue(1): 41-45