后纵韧带骨化症(OPLL)是脊柱外科常见病之一。附着于椎体后缘的后纵韧带在多因素作用下形成骨化物,骨化物持续生长造成脊髓和神经根受压,平时可无症状或症状不典型,一旦遇到外伤,即使是轻微外力也可导致严重的四肢感觉、运动、反射及二便功能障碍,甚至瘫痪,严重降低患者生活质量,给家庭及社会带来沉重负担。OPLL在东亚地区高发,发生率为0.4% ~ 3.0%[1],而经CT三维重建检查发现,存在颈脊髓压迫症状的人群中OPLL检出率高达18.22%[2]。目前,手术是OPLL最佳的治疗方案[3],但手术并不能完全解决骨化物继续生长或其他部位新发骨化的问题。因此,临床上需要有效的手段从发病环节阻断疾病的发生与发展。有研究[4-5]表明,遗传因素与环境因素共同参与了OPLL的发生与发展,但仍没有研究明确揭示OPLL发生与发展的原因及针对病因的药物治疗方案。本文通过查阅近年国内外OPLL病因学研究文献并对其进行梳理,从遗传因素、机械应力、生物标志物及生活方式对OPLL发生、发展的影响展开分析,并简要介绍目前研究的不足及最新研究趋势,综述如下。

1 遗传因素 1.1 编码蛋白基因1984年,Tsuyama等[6]发现OPLL有高遗传率的特征。20世纪90年代开始,人类基因组计划(HGP)的提出与兴起吸引了学界对OPLL患者进行大量测序研究,发现诸多易感基因位点与OPLL的发生、发展相关。核苷酸焦磷酸酶(NPPS)基因多态性即是较早期发现之一[7]。此外,双生子连锁分析、候选基因关联分析发现,与OPLL发生相关的易感基因位点多态性包括编码ⅩⅦ型胶原α1链(COL17A1)、Ⅵ型胶原α1链(COL6A1)、Ⅺ型胶原蛋白α2链(COL11A2)、骨形态发生蛋白-2(BMP-2)、BMP-4、BMP-9、血管紧张素转换酶(ACE)、BH3相互作用结构域死亡激动剂(BID)、runt相关转录因子2(RUNX2)、转化生长因子β受体2(TGFBR2)、转化生长因子β1(TGFB1)、维生素K环氧还原酶复合物亚基1(VKORC1)、γ干扰素(IFN-γ)、成纤维细胞生长因子受体1(FGFR1)、白介素15受体α亚基(IL15RA)、雌激素受体(ER)等的基因[8-10],其中编码BMP和胶原基因相关报道较多。但上述易感基因多是研究者选择目标基因进行PCR扩增并分析结果后发现,存在可研究的基因种类及数量有限、样本量较小且研究效率较低的问题,临床转化价值较低。

近年来,测序技术的进步和生物信息学的飞速发展为OPLL病因学研究带来新思路和新成果。全基因组测序研究发现了一批潜在的引起OPLL的基因及位点。Nakajima等[4, 11]对15 000余例日本OPLL患者进行全基因组关联分析,发现6个相关性最高的OPLL易感位点,并通过离体和在体实验证实了rs374810位点突变,通过影响启动子功能使RSPO2表达降低,进而激活经典Wnt/β-catenin信号通路,引起OPLL。Chen等[12]应用高通量测序技术对55例OPLL患者进行全基因组测序,发现COL6A1、COL11A2、FGFR1、BMP-2与OPLL发生相关。Wang等[13-16]对30例胸椎OPLL患者进行基因组测序及其相关基础研究发现,分别位于COL6A1基因c.1534G > A(p.Gly512Ser)和白介素17受体C(IL17RC)c.2275C > A(p.Leu759Ile)的有害突变与OPLL发生相关,突变亦导致其外周血中浓度显著增高。Liang等[17]对25例OPLL患者全基因组测序并分析后发现,3个基因上的4个有害突变与OPLL发生相关,分别位于COL6A6基因c.2716C > T(p.Arg906Cys)、COL9A1基因c.1946G > C(p.Gly649Ala)及TLR1基因c.301T > C(p.Ser101Pro)和c.171A > G(p.Ile57Met)。

上述文献大多仅报道测序发现,缺乏对突变位点引发OPLL机制的深入研究。即使部分基因在不同研究间得到多次证实,提升了结论的可信度,但亦有研究得出不同结论。Horikoshi等[18]的研究发现,TGFB3单核苷酸多态性(SNP)与OPLL显著相关,而与NPPS,TGFB1,COL11A2基因SNP无相关性。上述测序研究结果间的矛盾之处表明,OPLL具有高度遗传异质性和复杂的形成机制。未来还需通过多中心、大样本量的研究及多途径、多手段证实相关基因功能,以得到其与OPLL发生、发展的因果关系,经此才能真正阐明相关基因在OPLL病程中所起的作用,为今后对OPLL预防与精准化干预提供更坚实的基础。

1.2 非编码RNA(ncRNA)对OPLL患者转录本中ncRNA与OPLL发生关系的研究是近几年来OPLL病因学研究领域新出现的研究内容。目前,引发OPLL的基因中,研究最广泛的是编码蛋白基因,然而,这些基因仅占基因组的1.5%。ncRNA数量庞大且同样对细胞生长发育的调控及疾病的发生、发展起关键作用,但是,其潜在的调控网络与具体机制尚待进一步阐述。高通量测序技术的出现及生物信息分析方法的应用使对数量庞大的ncRNA研究成为可能。近年有学者对微小RNA(miRNA)和长链非编码RNA(lncRNA)与OPLL之间的关系进行研究,推动了OPLL病因学研究的进展及对疾病的理解。

Xu等[19-20]在对骨化及无骨化患者韧带组织的原代细胞高通量测序后分析发现,在记录到的1 520个有效miRNA中,218个miRNA表达2倍上调或下调。作者利用生物信息学方法,通过比对RNA数据库预测可能的miRNA/mRNA调控网络。为了验证所构建的调控网络的正确性,作者通过RT-PCR分析4例OPLL和4例无骨化患者的后纵韧带细胞的RNA表达情况,检测结果与测序结果高度相似。其后,作者合成上调最显著的5个miRNA并将其转染入后纵韧带细胞中,以验证相关miRNA的功能,与对照组相比,转染组成骨相关基因表达上调,矿化结节显著增多,尤其是miR-10a-5p促进成骨效果最为显著。在此基础上,作者还发现高表达的miR-10a通过抑制ID3促进RUNX2表达,使成骨分化增强,在OPLL发生中起一定作用。Lim等[21]在一项纳入207例颈椎OPLL患者和200例对照者的研究中发现,miR-146aC > G等4个位点多态性的不同组合与OPLL发生风险显著相关。Yuan等[22]的研究发现,肺腺癌相关转录子(MALAT)lncRNA在OPLL细胞内表达增高,其可能通过发挥miR-1的海绵作用,降低miR-1对缝隙连接蛋白43(Cx43)的抑制作用引起成骨相关基因的高表达,最终导致OPLL的发生。亦有学者发现,miR218[23]、miR-563[19, 24]及X染色体失活特异性转录因子(XIST)lncRNA[25]与OPLL发生相关,并通过系列实验证实其促进成骨及在OPLL发生中的机制。

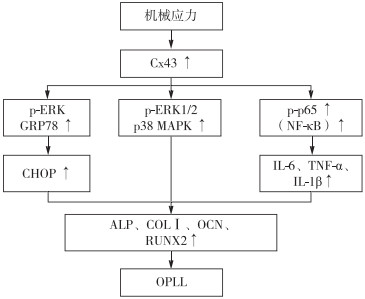

2 机械应力机械应力在骨的生长和发育中起到重要作用,力学的平衡与稳定性是目前脊柱外科研究热点之一。后纵韧带位于椎体后缘,其参与维持脊柱的稳定与平衡,长期受到应力作用。因此,机械应力是否与OPLL发生、发展相关吸引了诸多学者的兴趣。1996年,Matsunaga等[26]报道OPLL的进展与椎间盘的异常应力分布高度相关,韧带骨化的进展最常分布于椎间盘拉伸扭曲区域。近年来,Sugita等[27]对OPLL患者术中标本进行研究,发现Ihh信号通路信号分子,如甲状旁腺激素相关蛋白(PTHrP)和Y染色体中性别决定区相关的高迁移率组框-9(SOX-9)等,在骨化组织及软骨细胞中表达显著增高。将骨化和无骨化患者后纵韧带细胞置于应力状态下培养24 h后进行微阵列分析,研究差异表达的基因,测序结果对比KEGG数据库发现,和无骨化患者相比,骨化患者表达上调的24个基因中有7个(Ihh、SMO、PTCH1、PTCH2、Gli2、Gli3及STK36)定位于Ihh信号通路,且免疫组化染色结果显示上述Ihh通路信号分子亦呈强阳性,佐证了生物信息分析结果。Zhang等[28]将从OPLL患者韧带提取的细胞进行离体实验发现,机械应力同样可以使OPLL患者韧带细胞内波形蛋白表达显著降低;siRNA沉默波形蛋白亦导致骨钙素(OCN)、碱性磷酸酶(ALP)和COLⅠ表达水平升高,因此,作者提出机械应力刺激可降低波形蛋白的表达水平,进而促进细胞成骨分化引发OPLL。Chen等[29]和Shi等[30]的研究发现,细胞内Cx43是机械应力引起OPLL的核心因子(图 1)。与非OPLL人群相比,OPLL患者韧带Cx43和磷酸化细胞外信号调节激酶(p-ERK)表达水平显著上升,机械应力通过内质网感受应力变化并改变Cx43的表达水平,该蛋白通过p38丝裂原活化蛋白激酶(p38 MAPK)、核因子-κB(NF-κB)和ERK等信号通路诱导OPLL的发生。

|

图 1 机械应力通过Cx43引起OPLL |

亦有研究发现,机械应力通过刺激ATP产生和嘌呤受体高表达核结合因子α1(Cbfa1)、胰岛素样生长因子-1(IGF-1)、结缔组织生长因子、前列腺素I2(PGI2)、内皮素-1(ET-1)和甲状旁腺激素等引起OPLL或加速其进展[31-32]。

3 生物标志物Tsuji等[33]对10例OPLL患者与10例健康志愿者进行血浆代谢组学分析发现,即使排除了糖尿病与高脂血症患者,OPLL组血浆酰基肉碱、棕榈酰肉碱、脂肪酸、甲状腺素、硫脯氨酸、血磷浓度显著高于对照组。Xu等[34]在分析OPLL患者韧带组织样本中miRNA表达差异的基础上,对比miRNA在骨化与无骨化患者血清中的浓度发现,循环中miR-10a-5p、miR-563和miR-210-3p浓度升高对OPLL有指导诊断的价值。Tsuru等[35]对OPLL患者和健康受试者进行了血清蛋白组学分析发现,血小板前碱性蛋白配体7(CXCL7)浓度显著降低,且CXCL7基因敲除鼠脊柱韧带亦出现骨化表型。Cai等[36]和Kawaguchi等[37]对比OPLL患者与健康志愿者以及进展和无进展OPLL患者血浆生物标志物发现,OPLL患者血清成纤维细胞生长因子-23(FGF-23)和超敏C反应蛋白(hs-CRP)水平更高,血磷值显著降低,且骨化进展组FGF-23和hs-CRP浓度高于无进展组,表明磷代谢、炎性反应及FGF-23在某种程度上也参与OPLL的发生、进展。

Feng等[38]和Ikeda等[39]的研究发现,女性OPLL患者体内瘦素浓度、瘦素/体质量指数比值均高于无骨化组,且瘦素可直接促进间充质干细胞向成骨细胞分化。Chen等[40]也报道与对照组相比,OPLL患者瘦素在转录和翻译水平均增高,并通过实验论证了瘦素和机械应力共同通过MAPK、JAK2-STAT3和PI3K/Akt信号通路诱导韧带细胞向成骨细胞分化,引起OPLL。关于血糖及胰岛素水平与OPLL的发生是否相关尚无一致结论[36, 41],高浓度胰岛素(1 000 mmol/L)可显著提升BMP-2介导的ALP表达和激活,可能通过该途径参与OPLL的发生、发展[42]。

有研究发现,OPLL患者脑脊液中IL-8[43],透明质酸(HA)[44]浓度显著增高。亦有文献报道OPLL患者LIM矿化蛋白-1(LMP-1)[45]、胰岛素样生长因子-1(IGF-1)、伴肌动蛋白相关锚定蛋白、胆绿素还原酶B、COL6A1、骨硬化蛋白(SOST)、Dickkopf相关蛋白1(DKK1)、衰老星形胶质细胞特异性诱导物质(OASIS)等含量改变[46-48](表 1)。

|

|

表 1 OPLL发病及进展相关生物标志物 |

除了上述因素,生活方式同样与OPLL发生相关。Chaput等[49]对患者性别、年龄、血压、脏器及皮下脂肪等进行评估发现,OPLL与年龄和高血压相关。Wang等[50]的一项病例对照研究发现,高盐饮食(OR=2.62)是OPLL的危险因素,每日肉类摄入是OPLL保护因素(OR=0.39),人群流行病学调查也有类似发现[50]。Washio等[5]的研究发现,每天6 ~ 8 h睡眠(OR=0.18)、按时就寝和起床等良好的睡眠习惯(OR=0.44)是OPLL的保护因素;适量锻炼、吸烟、饮酒等与OPLL的发生无相关性。

综上,生活方式一定程度上参与了OPLL的发生。但上述对OPLL患者生活方式的研究主要在日本进行,国内也很有必要对国人生活方式与OPLL发生及进展之间的关系进行多中心、大样本的研究。

5 总结与展望OPLL是一种以后纵韧带进行性骨化压迫脊髓和神经根引起感觉、运动等功能障碍为特征的退行性疾病,其发病隐匿,病程后期轻微外力即可导致瘫痪等严重后果。OPLL形成原因尚无定论,其可能机制为在遗传和非遗传因素共同作用下,韧带内细胞成分成骨分化增强,启动成骨相关过程,导致后纵韧带骨化物形成。目前研究已发现大量OPLL易感基因,并对其潜在的骨化形成机制进行了初步探究,同时对OPLL非遗传因素,如机械应力及生物标志物等的研究亦有长足的进展。

近年来,测序技术的进步及生物信息学的兴起和普及为OPLL病因学研究带来了一系列新成果,该领域结合了测序、计算机、基础医学和临床医学等多学科,共同参与对OPLL发生机制的探索。其通过计算机算法将高通量测序技术产生的海量数据与数据库进行比对挖掘OPLL可能的发生机制,后续辅以实验数据分析证实结果的可靠性,这一趋势与国内外生物信息学的飞速发展密切相关,为将来深入探究OPLL发生机制及干预靶点提供了新思路与新方向。

| [1] |

Matsunaga S, Sakou T. Ossification of the posterior longitudinal ligament of the cervical spine: etiology and natural history[J]. Spine(Phila Pa 1976), 2012, 37(5): E309-E314. DOI:10.1097/BRS.0b013e318241ad33 |

| [2] |

Liao X, Jin Z, Shi L, et al. Prevalence of ossification of posterior longitudinal ligament in patients with degenerative cervical myelopathy: cervical spine 3d CT observations in 7210 cases[J]. Spine(Phila Pa 1976), 2020, 45(19): 1320-1328. DOI:10.1097/BRS.0000000000003526 |

| [3] |

Wu JC, Chen YC, Liu L, et al. Conservatively treated ossification of the posterior longitudinal ligament increases the risk of spinal cord injury: a nationwide cohort study[J]. J Neurotrauma, 2012, 29(3): 462-468. DOI:10.1089/neu.2011.2095 |

| [4] |

Nakajima M, Takahashi A, Tsuji T, et al. A genome-wide association study identifies susceptibility loci for ossification of the posterior longitudinal ligament of the spine[J]. Nat Genet, 2014, 46(9): 1012-1016. DOI:10.1038/ng.3045 |

| [5] |

Washio M, Kobashi G, Okamoto K, et al. Sleeping habit and other life styles in the prime of life and risk for ossification of the posterior longitudinal ligament of the spine(OPLL): a case-control study in Japan[J]. J Epidemiol, 2004, 14(5): 168-173. DOI:10.2188/jea.14.168 |

| [6] |

Tsuyama N. Ossification of the posterior longitudinal ligament of the spine[J]. Clin Orthop Relat Res, 1984(184): 71-84. |

| [7] |

Nakamura I, Ikegawa S, Okawa A, et al. Association of the human NPPS gene with ossification of the posterior longitudinal ligament of the spine(OPLL)[J]. Hum Genet, 1999, 104(6): 492-497. DOI:10.1007/s004390050993 |

| [8] |

唐一钒, 陈雄生. 后纵韧带骨化症发病机制的研究进展[J]. 中华骨科杂志, 2018, 38(24): 1545-1552. DOI:10.3760/cma.j.issn.0253-2352.2018.24.009 |

| [9] |

Pope DH, Davies BM, Mowforth OD, et al. Genetics of degenerative cervical myelopathy: a systematic review and meta-analysis of candidate gene studies[J]. J Clin Med, 2020, 9(1): 282. DOI:10.3390/jcm9010282 |

| [10] |

刘洋, 袁文. 脊柱后纵韧带骨化性疾病的基础研究进展[J]. 脊柱外科杂志, 2010, 8(2): 120-123. DOI:10.3969/j.issn.1672-2957.2010.02.015 |

| [11] |

Nakajima M, Kou I, Ohashi H, et al. Identification and functional characterization of RSPO2 as a susceptibility gene for ossification of the posterior longitudinal ligament of the spine[J]. Am J Hum Genet, 2016, 99(1): 202-207. DOI:10.1016/j.ajhg.2016.05.018 |

| [12] |

Chen X, Guo J, Cai T, et al. Targeted next-generation sequencing reveals multiple deleterious variants in OPLL-associated genes[J]. Sci Rep, 2016, 6: 26962. DOI:10.1038/srep26962 |

| [13] |

Wang P, Liu X, Zhu B, et al. Identification of susceptibility loci for thoracic ossification of the posterior longitudinal ligament by whole-genome sequencing[J]. Mol Med Rep, 2018, 17(2): 2557-2564. |

| [14] |

Wang P, Liu X, Zhu B, et al. Association of IL17RC and COL6A1 genetic polymorphisms with susceptibility to ossification of the thoracic posterior longitudinal ligament in Chinese patients[J]. J Orthop Surg Res, 2018, 13(1): 109. DOI:10.1186/s13018-018-0817-y |

| [15] |

Wang P, Liu X, Liu X, et al. IL17RC affects the predisposition to thoracic ossification of the posterior longitudinal ligament[J]. J Orthop Surg Res, 2019, 14(1): 210. DOI:10.1186/s13018-019-1253-3 |

| [16] |

Wang P, Liu X, Kong C, et al. Potential role of the IL17RC gene in the thoracic ossification of the posterior longitudinal ligament[J]. Int J Mol Med, 2019, 43(5): 2005-2014. |

| [17] |

Liang C, Wang P, Liu X, et al. Whole-genome sequencing reveals novel genes in ossification of the posterior longitudinal ligament of the thoracic spine in the Chinese population[J]. J Orthop Surg Res, 2018, 13(1): 324. DOI:10.1186/s13018-018-1022-8 |

| [18] |

Horikoshi T, Maeda K, Kawaguchi Y, et al. A large-scale genetic association study of ossification of the posterior longitudinal ligament of the spine[J]. Hum Genet, 2006, 119(6): 611-616. DOI:10.1007/s00439-006-0170-9 |

| [19] |

Xu C, Chen Y, Zhang H, et al. Integrated microRNA-mRNA analyses reveal OPLL specific microRNA regulatory network using high-throughput sequencing[J]. Sci Rep, 2016, 6: 21580. DOI:10.1038/srep21580 |

| [20] |

Xu C, Zhang H, Gu W, et al. The microRNA-10a/ID3/RUNX2 axis modulates the development of ossification of posterior longitudinal ligament[J]. Sci Rep, 2018, 8(1): 9225. DOI:10.1038/s41598-018-27514-x |

| [21] |

Lim JJ, Shin DA, Jeon YJ, et al. Association of miR-146a, miR-149, miR-196a2, and miR-499 polymorphisms with ossification of the posterior longitudinal ligament of the cervical spine[J]. PLoS One, 2016, 11(7): e0159756. DOI:10.1371/journal.pone.0159756 |

| [22] |

Yuan X, Guo Y, Chen D, et al. Long non-coding RNA MALAT1 functions as miR-1 sponge to regulate Connexin 43-mediated ossification of the posterior longitudinal ligament[J]. Bone, 2019, 127: 305-314. DOI:10.1016/j.bone.2019.06.019 |

| [23] |

吴深深, 薛敏涛, 孙柏峰, 等. 微RNA-218通过抑制RUNX2及Ⅰ型胶原基因表达延缓后纵韧带骨化[J]. 脊柱外科杂志, 2019, 17(4): 257-261. DOI:10.3969/j.issn.1672-2957.2019.04.008 |

| [24] |

张浩, 徐辰, 刘洋, 等. 微小RNA-563通过靶向抑制SMURF1基因促进后纵韧带细胞成骨分化的体外研究[J]. 中华外科杂志, 2017, 55(3): 203-207. DOI:10.3760/cma.j.issn.0529-5815.2017.03.008 |

| [25] |

Liao X, Tang D, Yang H, et al. Long non-coding RNA XIST may influence cervical ossification of the posterior longitudinal ligament through regulation of miR-17-5P/AHNAK/BMP2 signaling pathway[J]. Calcif Tissue Int, 2019, 105(6): 670-680. DOI:10.1007/s00223-019-00608-y |

| [26] |

Matsunaga S, Sakou T, Taketomi E, et al. Effects of strain distribution in the intervertebral discs on the progression of ossification of the posterior longitudinal ligaments[J]. Spine(Phila Pa 1976), 1996, 21(2): 184-189. DOI:10.1097/00007632-199601150-00005 |

| [27] |

Sugita D, Nakajima H, Kokubo Y, et al. Cyclic tensile strain facilitates ossification of the cervical posterior longitudinal ligament via increased Indian hedgehog signaling[J]. Sci Rep, 2020, 10(1): 7231. DOI:10.1038/s41598-020-64304-w |

| [28] |

Zhang W, Wei P, Chen Y, et al. Down-regulated expression of vimentin induced by mechanical stress in fibroblasts derived from patients with ossification of the posterior longitudinal ligament[J]. Eur Spine J, 2014, 23(11): 2410-2415. DOI:10.1007/s00586-014-3394-8 |

| [29] |

Chen D, Chen Y, Li T, et al. Role of Cx43-mediated NFкB signaling pathway in ossification of posterior longitudinal ligament: an in vivo and in vitro study[J]. Spine(Phila Pa 1976), 2017, 42(23): E1334-E1341. DOI:10.1097/BRS.0000000000002165 |

| [30] |

Shi L, Shi G, Li T, et al. The endoplasmic reticulum stress response participates in connexin 43-mediated ossification of the posterior longitudinal ligament[J]. Am J Transl Res, 2019, 11(7): 4113-4125. |

| [31] |

Nam DC, Lee HJ, Lee CJ, et al. Molecular pathophysiology of ossification of the posterior longitudinal ligament (OPLL)[J]. Biomol Ther(Seoul), 2019, 27(4): 342-348. DOI:10.4062/biomolther.2019.043 |

| [32] |

Furukawa K. Current topics in pharmacological research on bone metabolism: molecular basis of ectopic bone formation induced by mechanical stress[J]. J Pharmacol Sci, 2006, 100(3): 201-204. DOI:10.1254/jphs.FMJ05004X4 |

| [33] |

Tsuji T, Matsumoto M, Nakamura M, et al. Metabolite profiling of plasma in patients with ossification of the posterior longitudinal ligament[J]. J Orthop Sci, 2018, 23(6): 878-883. DOI:10.1016/j.jos.2018.07.001 |

| [34] |

Xu C, Zhang H, Zhou W, et al. MicroRNA-10a, -210, and -563 as circulating biomarkers for ossification of the posterior longitudinal ligament[J]. Spine J, 2019, 19(4): 735-743. DOI:10.1016/j.spinee.2018.10.008 |

| [35] |

Tsuru M, Ono A, Umeyama H, et al. Ubiquitin-dependent proteolysis of CXCL7 leads to posterior longitudinal ligament ossification[J]. PLoS One, 2018, 13(5): e0196204. DOI:10.1371/journal.pone.0196204 |

| [36] |

Cai GD, Zhu ZC, Wang JQ, et al. Multiplex analysis of serum hormone and cytokine in patients with cervical cOPLL: towards understanding the potential pathogenic mechanisms[J]. Growth Factors, 2017, 35(4-5): 171-178. DOI:10.1080/08977194.2017.1401617 |

| [37] |

Kawaguchi Y, Kitajima I, Nakano M, et al. Increase of the Serum FGF-23 in ossification of the posterior longitudinal ligament[J]. Global Spine J, 2019, 9(5): 492-498. DOI:10.1177/2192568218801015 |

| [38] |

Feng B, Cao S, Zhai J, et al. Roles and mechanisms of leptin in osteogenic stimulation in cervical ossification of the posterior longitudinal ligament[J]. J Orthop Surg Res, 2018, 13(1): 165. DOI:10.1186/s13018-018-0864-4 |

| [39] |

Ikeda Y, Nakajima A, Aiba A, et al. Association between serum leptin and bone metabolic markers, and the development of heterotopic ossification of the spinal ligament in female patients with ossification of the posterior longitudinal ligament[J]. Eur Spine J, 2011, 20(9): 1450-1458. DOI:10.1007/s00586-011-1688-7 |

| [40] |

Chen S, Zhu H, Wang G, et al. Combined use of leptin and mechanical stress has osteogenic effects on ossification of the posterior longitudinal ligament[J]. Eur Spine J, 2018, 27(8): 1757-1766. DOI:10.1007/s00586-018-5663-4 |

| [41] |

Shin J, Choi JY, Kim YW, et al. Quantification of risk factors for cervical ossification of the posterior longitudinal ligament in Korean populations: a nationwide population-based case-control study[J]. Spine(Phila Pa 1976), 2019, 44(16): E957-E964. DOI:10.1097/BRS.0000000000003027 |

| [42] |

Li H, Liu D, Zhao CQ, et al. Insulin potentiates the proliferation and bone morphogenetic protein-2-induced osteogenic differentiation of rat spinal ligament cells via extracellular signal-regulated kinase and phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase[J]. Spine(Phila Pa 1976), 2008, 33(22): 2394-2402. DOI:10.1097/BRS.0b013e3181838fe5 |

| [43] |

Ito K, Matsuyama Y, Yukawa Y, et al. Analysis of interleukin-8, interleukin-10, and tumor necrosis factor-alpha in the cerebrospinal fluid of patients with cervical spondylotic myelopathy[J]. J Spinal Disord Tech, 2008, 21(2): 145-157. DOI:10.1097/BSD.0b013e31806458b3 |

| [44] |

Sakayama K, Kidani T, Sugawara Y, et al. Elevated concentration of hyaluronan in the cerebrospinal fluid is a secondary marker of spinal disorders: hyaluronan in the cerebrospinal fluid in patients with spinal disorders[J]. J Spinal Disord Tech, 2006, 19(4): 262-265. DOI:10.1097/01.bsd.0000203944.65803.17 |

| [45] |

蔡国栋, 孔德谦, 王俊勤, 等. LIM矿化蛋白-1与颈椎后纵韧带骨化相关性的实验研究[J]. 中国矫形外科杂志, 2015, 23(7): 649-653. |

| [46] |

Zhang Y, Liu B, Shao J, et al. Proteomic profiling of posterior longitudinal ligament of cervical spine[J]. Int J Clin Exp Med, 2015, 8(4): 5631-5639. |

| [47] |

Yayama T, Mori K, Okumura N, et al. Wnt signaling pathway correlates with ossification of the spinal ligament: a microRNA array and immunohistochemical study[J]. J Orthop Sci, 2018, 23(1): 26-31. DOI:10.1016/j.jos.2017.09.024 |

| [48] |

Chen Y, Yang H, Miao J, et al. Roles of the endoplasmic reticulum stress transducer OASIS in ossification of the posterior longitudinal ligament[J]. Clin Spine Surg, 2017, 30(1): E19-E24. DOI:10.1097/BSD.0b013e3182908c21 |

| [49] |

Chaput CD, Siddiqui M, Rahm MD. Obesity and calcification of the ligaments of the spine: a comprehensive CT analysis of the entire spine in a random trauma population[J]. Spine J, 2019, 19(8): 1346-1353. DOI:10.1016/j.spinee.2019.03.003 |

| [50] |

Wang PN, Chen SS, Liu HC, et al. Ossification of the posterior longitudinal ligament of the spine. A case-control risk factor study[J]. Spine(Phila Pa 1976), 1999, 24(2): 142-145. DOI:10.1097/00007632-199901150-00010 |

| [51] |

Okamoto K, Kobashi G, Washio M, et al. Dietary habits and risk of ossification of the posterior longitudinal ligaments of the spine(OPLL): findings from a case-control study in Japan[J]. J Bone Miner Metab, 2004, 22(6): 612-617. DOI:10.1007/s00774-004-0531-1 |

2021, Vol.19

2021, Vol.19  Issue(2): 130-135

Issue(2): 130-135