2. 北京大学第三医院骨科, 北京 100191;

3. 河南省人民医院脊柱脊髓外科, 郑州 463599

2. Department of Orthopaedics, Peking University Third Hospital, Beijing 100191, China;

3. Department of Spinal and Spinal Cord Surgery, Henan Provincial People's Hospital, Zhengzhou 463599, Henan, China

2021年我国有近1/5的人口>60岁[1]。随着人口的深度老龄化,至少36%的60岁以上老人会出现因脊柱畸形产生的腰背痛[2]。成人退行性脊柱侧凸(ADS)是在长期的异常生物力学作用下,骨、小关节、椎间盘、肌肉和韧带多种组织发生退行性变引起的宏观现象,主要集中于老年人群[3]。ADS会导致脊柱节段性或整体不稳定,严重的脊柱节段性不稳或整体失衡会引发临床症状,如腰痛、活动受限等,部分患者有明确的神经压迫症状[4-5]。ADS是个多平面的问题,但60%以上的ADS都涉及到矢状面失衡[6]。手术矫形可以恢复力线、减轻神经压迫,改善患者生活质量,但是老年群体组织器官代偿功能弱,且常伴有各种基础疾病,手术风险大,术后并发症多,如术中大出血,矫正失败,术后断钉、断棒,邻椎退行性变加速,伤口感染等,影响预后[7-9]。本研究探讨可能影响ADS预后的因素,为制订ADS手术策略提供借鉴。

1 资料与方法 1.1 一般资料纳入标准:①年龄>55岁。②影像学上需满足下列条件之一。冠状面脊柱侧凸Cobb角≥20°,矢状面垂直偏距(SVA)≥5 cm,腰椎前凸角(LL)-骨盆入射角(PI)>10°,骨盆倾斜角(PT)≥25°,胸椎后凸角(TK)≥60°。③须融合固定节段≥2个。排除标准:①脊柱手术史;②重度骨质疏松;③强直性脊柱炎或类风湿关节炎等风湿免疫性疾病;④外伤、感染或肿瘤引起的脊柱畸形。根据上述标准,纳入2018年5月—2020年5月应急总医院采用后路融合内固定术矫形的ADS患者79例,其中男36例、女43例,年龄为(58±20)岁,体质量指数(BMI)为(29±9)kg/m2,骨密度T值为-1.9±0.8。所有患者术前、术后影像资料完整,随访均>2年。

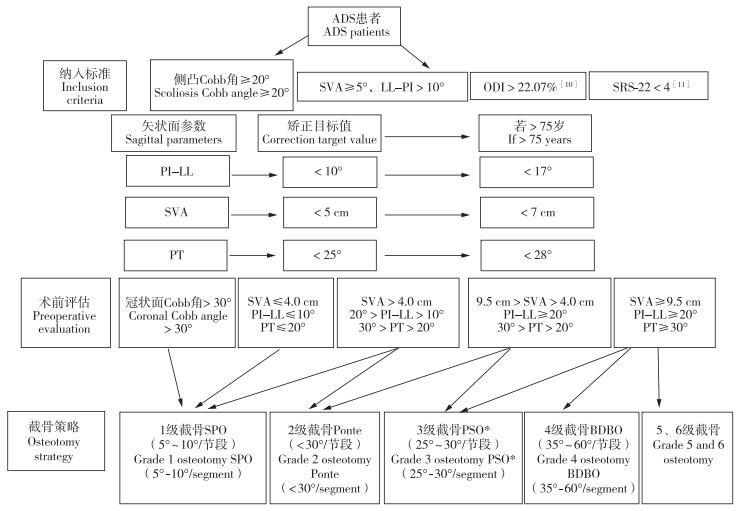

1.2 手术方法采用全身麻醉,取俯卧位,后正中入路,逐层剥离,显露椎板、关节突及横突基底,置入椎弓根螺钉。根据矫正程度选用相应的截骨方法(图 1)[10-12],并根据神经压迫的责任节段进行减压。选择上端固定椎(UIV)和下端固定椎(LIV)的原则是融合不能止于顶椎,应涵盖交界性后凸,包括严重的侧向滑移椎和前后滑椎,UIV应为水平椎。此外,UIV一般选择主弯近端的第一个中立椎,一般建议固定在T10,若T11、T12在上端椎以上或T11/T12、T12/L1椎间盘无明显退行性变,可选择T11、T12甚至L1作为UIV;在LIV的选择上,若L5/S1椎间盘没有明显退行性变,可固定至L5,否则应固定至S1,若融合节段>3个,应考虑置入骶髂螺钉[13-14]。可在凸侧放置临时固定棒,截骨后选用钴铬钼合金棒,先于凹侧放置,适量撑开后,再放置凸侧金属棒,加压过程中注意观察硬膜形态,并与神经电生理监测医师进行沟通,观察电生理波形变化。ADS矫形应以加压为主、撑开为辅,必要时给予人工椎体植入等行前柱重建。术中透视观察矢状面及冠状面力线,确认满意后,冲洗伤口,逐层缝合关闭伤口,放置负压引流管。术后观察引流量及引流液颜色,一般在引流量<150 mL/d或手术后72 h内拔除引流管,若考虑脑脊液漏,应延长拔管时间至术后2周。

|

图 1 手术策略 Fig. 1 Surgical strategy 注:* LL矫正>30°大概率需要三柱截骨(3级及以上截骨),若TK>40°,应固定到近胸段。 Note: * Three column osteotomy(grade 3 and above) is required for LL correction>30°. If TK>40°, fixation including proximal thoracic segment should be performed. |

术前及术后2年采用Oswestry功能障碍指数(ODI)[10]评估功能、脊柱侧凸研究学会22项患者问卷(SRS-22)评分[11]评估生活质量、疼痛视觉模拟量表(VAS)评分[15]评估腰背和下肢痛情况,测量PT、PI、LL、SVA、冠状面平衡(C7铅垂线与骶骨中垂线的垂直距离)、T1骨盆角(T1PA)及PI-LL。记录并统计术后并发症发生情况。

1.4 统计学处理采用SPSS 20.0软件对数据进行统计分析。符合正态分布的计量资料以x±s表示,术前和术后2年数据比较采用配对t检验,组间比较采用独立样本t检验;计数资料以例数和百分数表示,数据比较采用χ2检验。采用logistic回归分析评价多变量对功能预后的影响。以P<0.05为差异有统计学意义。

2 结果所有手术顺利完成,术后2周内发生伤口感染6例(7.6%)、2周后伤口感染1例(1.3%),术后肌力下降至3级或更差5例(6.3%),肺部感染7例(8.9%),内固定失败9例(11.4%),翻修手术10例(12.7%)。术后总体并发症发生率为41.8%(33/79),其中轻症(经过对症处理后不会对预后、住院时间、再次手术及治疗费用等造成重大影响[16])和重症并发症发生率分别为27.8%(22/79)和13.9%(11/79)。

与术前比较,患者术后2年SRS-22评分、ODI、腰背痛VAS评分改善,矢状面失衡(SVA≥5 cm)患者比例降低,冠状面平衡、PT、PI-LL、T1PA减小,差异均有统计学意义(P<0.05,表 1)。

|

|

表 1 所有患者术前和术后2年临床功能评分及影像学参数 Tab. 1 Clinical function scores and radiographic parameters at pre-operation and postoperative 2 years |

根据术后2年ODI,将患者分为功能最差组(ODI≥50%)与功能最佳组(ODI≤15%),其中功能最差组21例,功能最佳组30例。功能最差组患者BMI、重症并发症发生率高于功能最佳组;术前SRS-22评分、ODI差于功能最佳组,术前矢状面失衡(SVA≥5 cm)患者比例高于功能最佳组;术后2年SRS-22评分、ODI、腰背和下肢痛VAS评分差于功能最佳组,矢状面失衡患者比例、PI-LL和T1PA高于功能最佳组;差异均有统计学意义(P<0.05,表 2)。

|

|

表 2 功能最差组与最佳组统计数据 Tab. 2 Statistical data of worst and best function groups |

多因素logistic回归分析结果显示,BMI、术前ODI、术后2年SVA和术后2年T1PA是影响术后功能的危险因素(比值比为0.875,95%置信区间为0.807~0.996,P<0.05;比值比为0.904,95%置信区间为0.883~0.967,P<0.05;比值比为0.991,95%置信区间为0.897~0.995,P<0.05;比值比为0.982,95%置信区间为0.958~0.998,P<0.05)。

3 讨论本研究结果表明,ADS矫形手术涉及的节段较多,出血量大,总体并发症发生率高。据美国多个脊柱矫形中心联合开展的前瞻性、多中心、大样本的临床研究[17]报道,术中并发症发生率为25.1%,围手术期总并发症(术后6周内)发生率达52.2%,术后迟发性并发症(术后6周及以上)发生率为42.6%;相关并发症主要包括近端交界性后凸、内固定失败和迟发性感染,与内固定相关的并发症占27.8%,其次是术后影像学上的不稳定及邻椎退行性变,其中28.2%的患者2年内需要翻修。有研究[7-9]报道,ADS手术并发症发生率达69%,术后2年的翻修率达28%;而先天性脊柱畸形手术并发症发生率仅为14%,术后5年的翻修率为18%;退行性脊柱疾病的手术并发症发生率只有21%,术后5年的翻修率为23%。本研究中,总体轻症并发症发生率为27.8%,重症并发症发生率为13.9%,其中功能最差组重症并发症的发生率高于功能最佳组,说明术后并发症可能影响患者术后的生活功能。从数据上看,本研究结果与既往研究数据趋势是一致的,但似乎比国外的并发症发生率要低,这可能是因为国内患者手术意愿较低,导致信息偏倚。

虽然ADS术后发生并发症的概率较高,但及时矫正矢状面畸形能提高患者的生活质量[18]。本研究结果显示,术后2年患者矢状面和冠状面力线均有改善,SVA>5 cm的患者所占的百分比由术前的86.1%下降至术后2年的21.5%,术后PI-LL明显变小,SRS-22评分、ODI和腰背痛VAS评分均较术前改善,说明矢状面畸形的矫正与术后功能和生活质量的改善直接相关。

目前依然有很多医师还没有足够重视脊柱的整体平衡,而是关注局部运动单元的稳定与否[19],但局部必须在整体中起作用,若不能识别矢状面力线不良,会影响患者的视物活动,增加肌肉无用性能耗,以代偿性地保持脊柱整体平衡,此过程可能会导致患者产生相应症状,进而对患者的生活质量造成负面影响。本研究主要对脊柱整体平衡进行分析,脊柱平衡情况主要通过观察冠状面上骶骨中垂线(CSVL)和矢状面上TK、SVA、PT、PI-LL及骶骨倾斜角(SS)。需要注意的是,国内研究多参考国外研究数据,可能与国人的参数有所不同[20-21]。这些力线参数的正常范围还会随着年龄增长而发生变化,60岁以上人群要做适当修正。有研究[22]认为,年龄越大,矢状面铅垂线(C7铅垂线、乳突中心铅垂线)越向前,在制订手术计划时,75岁以上人群的矫正目标可做适当修正:PT<28.5°,PI-LL<16.7°,SVA<78.1 mm(但不要为负值),T1PA<27.7°。但需要明确的是,PI=PT+SS,其中PI不会因为姿势的改变而改变,是一个比较可靠的力学指标。近年,业内在研究脊柱矢状面整体平衡的时候,认识到胸椎、腰椎及骨盆的代偿能够影响SVA,将T1PA作为SVA的补充参数,能够更为真实地反映矢状面整体平衡[23]。本研究结果提示,术后2年T1PA是功能恢复情况的预后因素,同样证明了这一点。还有研究[24-26]将颈椎和颈胸交界纳入进来,矢状面上选定头颅中点(乳突中点)的铅垂线,对于伴有严重颈椎退行性变的老年人来说,乳突头端中点或许是比C7铅垂线更好的力线参数。

本研究根据术后2年ODI将患者分为功能最差组与功能最佳组,结果显示,功能最差组患者术前矢状面失衡患者比例更高、术后2年PI-LL更大。Ferrero等[27]的前瞻性队列研究纳入28例ADS患者,结果显示,畸形较严重的患者肌肉体积较小,PI-LL>10°的患者6个肌群的脂肪浸润增加,术后功能与生活质量与肌肉体积相关,证明矢状面力线不良的患者预后差可能与肌肉脂肪浸润增加和肌肉体积减少相关。本研究中,术后功能最差组患者术前矢状面整体平衡状态、SRS-22评分、ODI也较功能最佳组差,说明术前矢状面整体平衡、ODI与SRS-22评分都与预后相关。

虽然矢状面平衡与冠状面平衡都很重要,但本研究多因素回归分析结果并未显示冠状面平衡与预后有相关性。一项前瞻性、多中心的研究[28]也表明脊柱矢状面的矫正与预后更为相关,而冠状面Cobb角的矫正更多地与自我形象改善相关,还有研究[29]表明冠状面力线与功能评分呈弱相关。总之,ADS手术矫形必须注重脊柱整体平衡,尽可能实现矢状面与冠状面的平衡,尤其是矢状面平衡,努力实现PI-LL<10°、SVA<5 cm、PT<25°、T1PA 0~25°。

本研究在制订手术策略时参考了成人脊柱侧凸SRS-SCHWAB分型[12],首先根据冠状面上侧凸的解剖位置及Cobb角进行分类(Cobb角>30°),然后根据关系预后3个最重要的矢状面指标SVA、PI-LL和PT对脊柱的矢状面进行分型。冠状面上主弯Cobb角>30°,矢状面上修正越严重,临床功能越差,越有手术治疗的必要性[30]。本研究根据畸形的严重程度,采取相应的截骨方法完成矫正,具体策略是LL矫正>30°大概率需要三柱截骨,若TK>40°,应固定到近胸段,以降低近端交界性后凸的发生率和内固定失败的风险[12]。但手术与否、手术方案如何还需要根据患者失衡是否能够代偿及主诉症状来确定[31]。若患者不能耐受大的矫正手术,可通过短节段减压融合手术(如斜外侧腰椎椎间融合术)来解决神经压迫问题[32],甚至可尝试采用脊柱内窥镜技术进行局部减压[33]。

综上,手术矫形能够改善ADS患者生活质量,BMI、术前ODI、术后2年SVA和术后2年T1PA是预后的影响因素,应基于脊柱矢状面整体平衡状态制订ADS手术策略。本研究的意义:①较高的并发症发生率告诫脊柱外科医师ADS矫形手术并不因常见而简单;②深刻理解脊柱整体平衡方能制订正确的矫形方案;③矫形手术应尽可能使患者脊柱恢复到正常的力学范围(PI-LL≤10°,SVA<5 cm,PT<25°,T1PA<25°);④70岁以上患者矢状面参数应做适当修正(PI-LL<17°,SVA<7cm,PT<28°)。本研究为非随机、非匹配的回顾性研究,可能存在混杂偏倚;样本量有限、缺乏长期随访结果、高龄患者理解误差等原因可能引起信息偏倚。在今后的研究中,应着重开展多中心、随机对照研究,提高证据等级;还需要开展微创治疗ADS的新探索,降低手术并发症发生率,加速术后康复。

| [1] |

国家统计局. 中国人口老龄化数据第七次全国人口普查主要数据情况[EB/OL]. (2021-05-02)[2022-12-17]. http://www.stats.gov.cn/tjsj/zxfb/202105/t20210510_1817176.html.

|

| [2] |

Mcaviney J, Roberts C, Sullivan B, et al. The prevalence of adult de novo scoliosis: a systematic review and meta-analysis[J]. Eur Spine J, 2020, 29(12): 2960-2969. DOI:10.1007/s00586-020-06453-0 |

| [3] |

Ferrero E, Skalli W, Khalifé M, et al. Volume of spinopelvic muscles: comparison between adult spinal deformity patients and asymptomatic subjects[J]. Spine Deform, 2021, 9(6): 1617-1624. DOI:10.1007/s43390-021-00357-9 |

| [4] |

段煜东, 张子程, 李博, 等. 骨质疏松参与退行性脊柱侧凸发病的研究现状[J]. 第二军医大学学报, 2021, 42(12): 1402-1407. |

| [5] |

Mannion AF, Elfering A, Bago J, et al. Factor analysis of the SRS-22 outcome assessment instrument in patients with adult spinal deformity[J]. Eur Spine J, 2018, 27(3): 685-699. DOI:10.1007/s00586-017-5279-0 |

| [6] |

Schwab F, Dubey A, Gamez L, et al. Adult scoliosis: prevalence, SF-36, and nutritional parameters in an elderly volunteer population[J]. Spine(Phila Pa 1976), 2005, 30(9): 1082-1085. DOI:10.1097/01.brs.0000160842.43482.cd |

| [7] |

Soroceanu A, Burton DC, Oren JH, et al. Medical complications after adult spinal deformity surgery[J]. Spine(Phila Pa 1976), 2016, 41(22): 1718-1723. DOI:10.1097/BRS.0000000000001636 |

| [8] |

Sugawara R, Takeshita K, Inomata Y, et al. The Japanese scoliosis society morbidity and mortality survey in 2014: the complication trends of spinal deformity surgery from 2012 to 2014[J]. Spine Surg Relat Res, 2019, 3(3): 214-221. DOI:10.22603/ssrr.2018-0067 |

| [9] |

Mahesh B, Upendra B, Vijay S, et al. Complication rate during multilevel lumbar fusion in patients above 60 years[J]. Indian J Orthop, 2017, 51(2): 139-146. DOI:10.4103/0301-5742.204612 |

| [10] |

Fairbank JC, Couper J, Davies JB, et al. The Oswestry low back pain disability questionnaire[J]. Physiotherapy, 1980, 66(8): 271-273. |

| [11] |

Asher M, Min Lai S, Burton D, et al. The reliability and concurrent validity of the scoliosis research society-22 patient questionnaire for idiopathic scoliosis[J]. Spine(Phila Pa 1976), 2003, 28(1): 63-69. DOI:10.1097/00007632-200301010-00015 |

| [12] |

Schwab F, Blondel B, Chay E, et al. The comprehensive anatomical spinal osteotomy classification[J]. Neurosurgery, 2014, 74(1): 112-120. DOI:10.1227/NEU.0000000000000182o |

| [13] |

Kuklo TR, Bridwell KH, Lewis SJ, et al. Minimum 2-year analysis of sacropelvic fixation and L5-S1 fusion using S1 and iliac screws[J]. Spine, 2001, 26(18): 1976-1983. DOI:10.1097/00007632-200109150-00007 |

| [14] |

Smith EJ, Kyhos J, Dolitsky R, et al. S2 alar iliac fixation in long segment constructs, a two- to five-year follow-up[J]. Spine Deform, 2018, 6(1): 72-78. DOI:10.1016/j.jspd.2017.05.004 |

| [15] |

Huskisson EC. Measurement of pain[J]. Lancet, 1974, 2(7889): 1127-1131. |

| [16] |

Carreon LY, Puno RM, Dimar JR 2nd, et al. Perioperative complications of posterior lumbar decompression and arthrodesis in older adults[J]. J Bone Jt Surg Am Vol, 2003, 85(11): 2089-2092. DOI:10.2106/00004623-200311000-00004 |

| [17] |

Smith JS, Klineberg E, Lafage V, et al. Prospective multicenter assessment of perioperative and minimum 2-year postoperative complication rates associated with adult spinal deformity surgery[J]. J Neurosurg Spine, 2016, 25(1): 1-14. DOI:10.3171/2015.11.SPINE151036 |

| [18] |

Passias PG, Segreto FA, Bortz CA, et al. Probability of severe frailty development among operative and nonoperative adult spinal deformity patients: an actuarial survivorship analysis over a 3-year period[J]. Spine J, 2020, 20(8): 1276-1285. DOI:10.1016/j.spinee.2020.04.010 |

| [19] |

Goel A. Indicators of spinal instability in degenerative spinal disease[J]. J Craniovert Jun Spine, 2020, 11(3): 155-156. DOI:10.4103/jcvjs.JCVJS_115_20 |

| [20] |

Zhou S, Xu F, Wang W, et al. Age-based normal sagittal alignment in Chinese asymptomatic adults: establishment of the relationships between pelvic incidence and other parameters[J]. Eur Spine J, 2020, 29(3): 396-404. DOI:10.1007/s00586-019-06178-9 |

| [21] |

Arima H, Dimar JR 2nd, Glassman SD, et al. Differences in lumbar and pelvic parameters among African American, Caucasian and Asian populations[J]. Eur Spine J, 2018, 27(12): 2990-2998. DOI:10.1007/s00586-018-5743-5 |

| [22] |

Jalai CM, Cruz DL, Diebo BG, et al. Full-body analysis of age-adjusted alignment in adult spinal deformity patients and lower-limb compensation[J]. Spine(Phila Pa 1976), 2017, 42(9): 653-661. DOI:10.1097/BRS.0000000000001863 |

| [23] |

Plachta SM, Israel H, Brechbuhler J, et al. Inter/intraobserver reliability of T1 pelvic angle(TPA), a novel radiographic measure for global sagittal deformity[J]. Spine(Phila Pa 1976), 2018, 43(21): E1290-E1296. DOI:10.1097/BRS.0000000000002689 |

| [24] |

Scheer JK, Tang JA, Smith JS, et al. Cervical spine alignment, sagittal deformity, and clinical implications: a review[J]. J Neurosurg Spine, 2013, 19(2): 141-159. DOI:10.3171/2013.4.SPINE12838 |

| [25] |

Ling FP, Chevillotte T, Leglise A, et al. Which parameters are relevant in sagittal balance analysis of the cervical spine? A literature review[J]. Eur Spine J, 2018, 27(Suppl 1): 8-15. |

| [26] |

Ferrero E, Guigui P, Khalifé M, et al. Global alignment taking into account the cervical spine with odontoid hip axis angle(OD-HA)[J]. Eur Spine J, 2021, 30(12): 3647-3655. DOI:10.1007/s00586-021-06991-1 |

| [27] |

Ferrero E, Skalli W, Lafage V, et al. Relationships between radiographic parameters and spinopelvic muscles in adult spinal deformity patients[J]. Eur Spine J, 2020, 29(6): 1328-1339. DOI:10.1007/s00586-019-06243-3 |

| [28] |

Cawley DT, Takemoto M, Boissiere L, et al. The impact of corrective surgery on health-related quality of life subclasses in adult scoliosis: will degree of correction prognosticate degree of improvement?[J]. Eur Spine J, 2021, 30(7): 2033-2039. DOI:10.1007/s00586-021-06786-4 |

| [29] |

Jeon CH, Chung NS, Chung HW, et al. Prospective investigation of Oswestry disability index and short form 36 subscale scores related to sagittal and coronal parameters in patients with degenerative lumbar scoliosis[J]. Eur Spine J, 2021, 30(5): 1164-1172. DOI:10.1007/s00586-021-06740-4 |

| [30] |

Smith JS, Klineberg E, Schwab F, et al. Change in classification grade by the SRS-Schwab Adult Spinal Deformity Classification predicts impact on health-related quality of life measures: prospective analysis of operative and nonoperative treatment[J]. Spine(Phila Pa 1976), 2013, 38(19): 1663-1671. DOI:10.1097/BRS.0b013e31829ec563 |

| [31] |

Terran J, Schwab F, Shaffrey CI, et al. The SRS-Schwab adult spinal deformity classification: assessment and clinical correlations based on a prospective operative and nonoperative cohort[J]. Neurosurgery, 2013, 73(4): 559-568. DOI:10.1227/NEU.0000000000000012 |

| [32] |

杜传超, 张衡, 梁辰, 等. 斜外侧腰椎椎间融合术中及术后并发症[J]. 脊柱外科杂志, 2020, 18(1): 6-9, 52. |

| [33] |

杜传超, 毛天立, 刘宇, 等. 脊柱内窥镜下腰椎斜外侧入路椎管减压和椎间融合技术介绍[J]. 临床外科杂志, 2020, 28(12): 1188-1191. DOI:10.3969/j.issn.1005-6483.2020.12.031 |

2024, Vol.22

2024, Vol.22  Issue(1): 5-11

Issue(1): 5-11