2. 昆明医科大学第二附属医院骨科, 昆明 650101

2. Department of Orthopaedics, Second Affiliated Hospital of Kunming Medical University, Kunming 650101, Yunnan, China

脊柱侧凸是指脊柱的一个或多个节段在冠状面、矢状面和横断面上偏离, 形成带有一个或多个曲度的三维脊柱畸形[1]。应用Cobb法测量站立位X线片上脊柱侧凸Cobb角 > 10°, 伴/不伴矢状面弯曲或横断面旋转定义为脊柱侧凸。脊柱侧凸按病因可分为特发性、先天性、神经肌肉源性和综合征性。Chiari畸形是由先天性发育异常导致的涉及脑干、小脑和上段脊髓的脊柱畸形, 主要病变特征为小脑扁桃体等结构疝入枕骨大孔以下, 分为Ⅰ ~ Ⅳ型, 其中Ⅰ型最为常见, 发生率为0.56% ~ 1.00%[2-3];脊髓空洞症则主要表现为脊髓中央管内异常液体积聚而呈筒样串联, 可在颈髓或上胸段脊髓几个节段内发生, 也可向上、下延展, 是最常见的椎管内畸形[4]。既往研究[5-7]显示, 20% ~ 60%的脊柱侧凸患者合并脊髓空洞症, 而以脊髓空洞症首诊的患者中25% ~ 85%合并不同程度脊柱侧凸[8-9]。此外, 脊柱侧凸也见于ChiariⅠ型畸形患者, 发生率为13% ~ 36%[6, 10-12]。在同时合并ChiariⅠ型畸形和脊髓空洞症的患者中, 脊柱侧凸的发生率为71% ~ 85%[13-15]。特发性脊柱侧凸(IS)的手术治疗方案目前已达成共识[16-17], 但合并ChiariⅠ型畸形和脊髓空洞症的脊柱侧凸进展更快、冠状面失衡发生率更高、主弯柔韧性和椎体旋转度更低、围手术期神经并发症更多[18-20], 其治疗方案尚未达成共识。Li等[21]的研究结果显示, 严重僵硬性脊髓空洞症相关性脊柱侧凸和严重僵硬性IS患者在接受基于椎弓根螺钉的后路脊柱矫形融合术治疗后可获得相似的影像学结果和矫形效果。本研究对合并ChiariⅠ型畸形和脊髓空洞症的脊柱侧凸患者及IS患者进行了病例配对研究, 进一步比较二者的影像学特征和矫形效果, 旨在为合并ChiariⅠ型畸形和脊髓空洞症的脊柱侧凸患者临床诊疗方法的选择提供参考, 现报告如下。

1 资料与方法 1.1 一般资料纳入标准: ①ChiariⅠ型畸形, 即小脑扁桃体下疝至枕骨大孔水平以下(≥5 mm)[22];②合并脊髓空洞症的脊柱侧凸, 且无明显神经功能受损表现, 美国脊髓损伤协会(ASIA)分级[23]为E级;③随访时间≥5年;④影像学及临床资料完整。排除标准: ①既往有神经外科手术史, 如枕骨大孔减压术、脊髓空洞分流术等;②既往有脊柱手术史;③其他原因引起的脊柱畸形, 包括先天性、结缔组织性、综合征性等;④继发于其他原因的脊髓空洞, 如脊髓栓系综合征、脊髓脊膜膨出、脊髓纵裂、脊髓肿瘤、创伤或感染性粘连性蛛网膜炎。

根据上述标准, 纳入2007年1月—2015年6月昆明医科大学第二附属医院采用一期后路脊柱矫形术治疗的22例合并ChiariⅠ型畸形和脊髓空洞症的脊柱侧凸患者(研究组)22例, 并选取同时期采用一期后路脊柱矫形术治疗的22例IS患者(IS组)进行1∶1配对。2组配对资料包括年龄、性别、主弯位置、侧凸数量、冠状面影像学参数等(表 1)。2组手术均由同一团队完成, 研究组患者术前谈话强调因神经轴发育异常而导致术中矫形时有神经损伤的风险, 尤其是ChiariⅠ型畸形和脊髓空洞征可能因矫形术而造成凹侧脊髓受压, 从而出现严重神经并发症可能。所有患者及家属均签署知情同意书。本研究经昆明医科大学第二附属医院伦理委员会审核备案。

|

|

表 1 2组患者配对情况 Tab. 1 Matched data of patients in 2 groups |

2组患者均采用一期后路脊柱矫形融合术治疗。全身麻醉后对软组织及关节突充分松解, 对松解后畸形变化不大或术前和术中神经电生理监测波幅变化较大的患者行后路全脊椎截骨术(PVCR), 其中研究组9例(男7例、女2例), IS组8例(男6例、女2例)。患者取俯卧位, 后正中切开后骨膜下剥离显露融合节段内的脊柱后部骨性结构, 并徒手置入椎弓根螺钉, 透视确认椎弓根螺钉位置无误后切除顶椎区拟截骨节段脊柱后方的椎板、小关节, 分别从凸侧、凹侧经椎弓根切除前方椎体及其相邻上、下节段椎间盘和软骨板, 并切除椎管前壁骨质结构, 完成对顶椎的全脊椎切除。建立矫形间隙后, 首先加压实现脊柱短缩, 继以开放/闭合及提拉/旋棒等矫形力获得矫形。若矫形后切除脊椎间隙残留高度过大, 以切除的自体骨块填充钛网并置入椎间隙, 促进融合维持稳定性;若椎间隙较小, 则以自体骨打压植骨。矫形完成后, 充分制作植骨床, 利用自体骨或同种异体骨进行植骨融合[24-25]。其余患者(研究组13例、IS组14例)行单纯矫形术, 全身麻醉后广泛剥离椎旁组织充分松解顶椎区, 先于凸侧钉棒加压获得大部分矫形, 再于凹侧上棒, 依靠器械提供提拉、旋棒等矫形力(术中注意脊柱整体力线), 矫形完成后充分制备植骨床, 利用自体骨或同种异体骨进行植骨融合。

所有手术均在神经电生理监测下进行, 监测信号包括运动诱发电位(MEP)和体感诱发电位(SEP), 以判断术中是否出现脊髓、神经损伤并发症, 于矫形开始前常规使用甲泼尼龙1 000 mg, 并分别在置钉完成、矫形开始及矫形结束时行Stagnara唤醒试验评估神经功能。

1.3 观察指标记录所有患者手术时间、预估出血量、融合节段数及螺钉密度等。在手术前后站立位脊柱全长正侧位X线片上测量并计算[26-31]主弯Cobb角、侧曲角、柔韧性、顶椎位置、冠状面平衡(C7铅垂线与骶骨中心垂直线间的水平偏离距离)、矢状面后凸角、胸椎后凸角(TK, T5上终板与T12下终板连线间的夹角)、腰椎前凸角(LL, L1上终板与S1上终板连线间的夹角)、矢状位垂直轴(SVA, C7铅垂线至S1后上缘间的水平距离)、畸形角度比(DAR)、矫形率及矫形丢失率。

主弯顶椎位置确定方法: 根据枕骨大孔以下椎体的数量把椎体节段转换成数值, 设置枕骨大孔水平为0, C1为1, 以此类推, L5为24, 椎间盘用上、下椎体的平均值表示[32-33]。柔韧性(%)=(术前站立位Cobb角-术前侧曲位Cobb角)/术前站立位Cobb角×100%[34]。DAR是主弯Cobb角与参与主弯构成的椎体节段数之比, 包括冠状面DAR(C-DAR)、矢状面DAR(S-DAR)和总DAR(T-DAR)[35]。螺钉密度(%)=螺钉的数量/(固定融合节段数×2)×100%[36]。矫形率(%)=(术前Cobb角-术后2周Cobb角)/术前Cobb角×100%;矫形丢失率(%)=(末次随访Cobb角-术后2周Cobb角)/(术前Cobb角-术后2周Cobb角)×100%[37]。所有影像学数据测量均由1名高年资影像科医师和1名高年资脊柱外科医师分别测量后共同得出。

1.4 统计学处理采用SPSS 22.0软件对数据进行统计分析, 符合正态分布的计量资料以x±s表示, 手术前后比较采用独立样本t检验, 组间比较采用配对样本t检验;计数资料以例数和百分数表示, 采用χ2检验;以P < 0.05为差异有统计学意义。

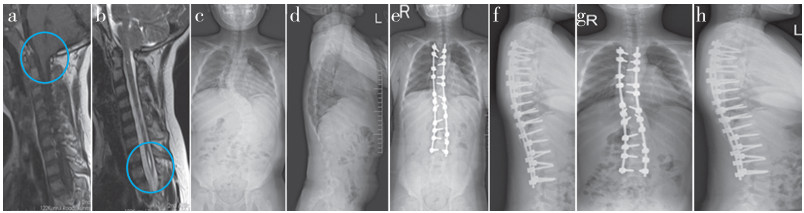

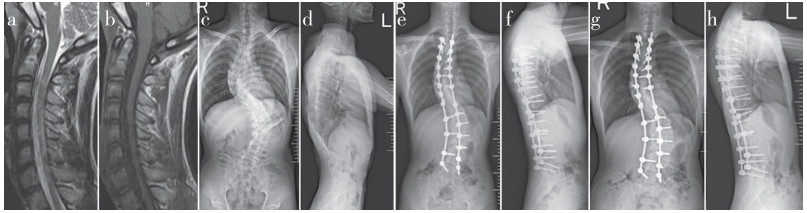

2 结果所有手术顺利完成, 研究组随访(6.2±1.2)年, IS组随访(6.2±1.1)年。2组患者接受PVCR治疗的比例、手术时间、预估出血量、融合节段数、螺钉密度差异均无统计学意义(P > 0.05, 表 2)。2组患者手术前后影像学参数差异均无统计学意义(P > 0.05, 表 2), 包括主弯Cobb角、冠状面平衡、矢状面后凸角、TK、LL、SVA、DAR(C-DAR、S-DAR和T-DAR)、术后及末次随访时冠状面和矢状面矫形率及其矫形丢失率。所有患者未发生螺钉松动、断裂、术后神经功能损伤等并发症, 术后ASIA分级仍均为E级, 末次随访时均获得骨性融合, 均未在后期施行枕骨大孔减压术。2组典型病例影像学资料见图 1、2。

|

|

表 2 统计数据 Tab. 2 Statistical data |

|

图 1 研究组典型病例影像学资料 Fig. 1 Imaging data of a typical case in study group 男, 11岁 a、b: 矢状位MRI示ChiariⅠ型畸形伴脊髓空洞症 c、d: 术前脊柱全长X线片示脊柱侧凸主弯Cobb角为75°伴脊柱后凸52° e、f: 术后2周脊柱全长X线片示侧凸和后凸被矫正至25°和33° g、h: 术后5年脊柱全长X线片示侧凸和后凸稳定在27°和36° Male, 11 years old a, b: Sagittal MRIs show Chiari Ⅰmalformation with syringomyelia c, d: Preoperative whole spine full length roentgenographs show scoliosis Cobb angle of main curve is 75° with kyphosis 52° e, f: Whole spine full length roentgenographs at postoperative 2 weeks show scoliosis and kyphosis are corrected to 25° and 33° g, h: Whole spine full length roentgenographs at postoperative 5 years show scoliosis and kyphosis are stabilized at 27° and 36° |

|

图 2 IS组典型病例影像学资料 Fig. 2 Imaging data of a typical case in IS group 男, 12岁 a、b: 矢状位MRI示椎管内未见异常 c、d: 术前脊柱全长X线片示脊柱侧凸主弯Cobb角78°伴脊柱后凸37° e、f: 术后2周脊柱全长X线片示侧凸和后凸被矫正至31°和34° g、h: 术后5.5年脊柱全长X线片示侧凸和后凸稳定在32°和36° Male, 11 years old a, b: Sagittal MRIs show no abnormality in spinal canal c, d: Preoperative whole spine full length roentgenographs show scoliosis Cobb angle of main curve is 78° with kyphosis 37° e, f: Whole spine full length roentgenographs at postoperative 2 weeks show scoliosis and kyphosis are corrected to 31° and 34° g, h: Whole spine full length roentgenographs at postoperative 5.5 years show scoliosis and kyphosis are stabilized at 27° and 36° |

椎管内畸形常与脊柱侧凸伴发, 合并ChiariⅠ型畸形和脊髓空洞症的患者中脊柱侧凸发生率为71% ~ 85%。然而, Chiari畸形的发生机制尚不清楚, 目前被广泛接受的是小脑扁桃体下疝学说[38-39]: 因胚胎发育过程中胚胎中轴叶轴旁的枕骨原节发育不良, 导致枕骨发育滞后于后颅窝脑组织, 从而继发小脑扁桃体下疝。有研究[40]发现, 在2/3的Chiari畸形患者可观察到小后颅凹和短斜坡, 且后颅凹越小, 小脑扁桃体下降率越高, 这也验证了该假说的可能性。Oldfield等[41]认为, 枕大孔区脑脊液循环梗阻时, 脑脊液可通过脊髓-血管间隙渗入脊髓实质内而产生空洞。Gardner等[42]认为, 在胚胎期第四脑室流出道延迟开放或开放不全导致中脑导水管与第四脑室脑脊液潴留, 阻塞脑脊液从枕大池流出进入脊髓蛛网膜下腔, 脑脊液搏动波向下冲击脊髓中央管, 致使中央管扩大, 并冲破中央管壁形成空洞。Williams[43]认为, 因枕大孔区蛛网膜下腔的梗阻使颅内椎管内压力失衡, 导致脑脊液循环产生垂直运动(即抽吸样效应), 造成脑脊液向中央管分流而形成空洞。此外, 还有脊髓栓系的牵拉学说[44], 血液-脊髓屏障破坏学说[45]等。尽管合并ChiariⅠ型畸形和脊髓空洞症的脊柱侧凸与IS之间的差异已有充分的文献报道, 但直接比较二者的影像学特征和矫形效果的文章有限。Diab等[46]发现, IS患者TK > 40°时更可能出现椎管内异常, 这意味着椎管内异常可能对矢状面参数有影响。本研究组采用1∶1配对的方式使2组患者的冠状面相似, 以确保2组术后获得的客观结果更具可比性。本研究结果显示, 2组患者在矢状面后凸角、TK、LL、S-DAR、SVA等矢状面参数方面差异无统计学意义, 且2组冠状面主弯柔韧性差异亦无统计学意义, 提示若冠状面参数已知, 则矢状面畸形相对稳定, 不受椎管内畸形的影响, 也提示ChiariⅠ型畸形和脊髓空洞症的存在并未使脊柱侧凸的柔韧性下降。

Lenke等[47]于2001年提出青少年特发性脊柱侧凸(AIS)的分型系统, 随后于2007年提出其治疗指南并被广泛运用于临床[48]。然而, ChiariⅠ型畸形合并脊髓空洞症的脊柱侧凸的最佳治疗方案目前尚未达成共识。传统治疗方案建议先行神经外科干预, 原因如下。①解除枕颈部压迫和阻塞以获得脊髓减压, 从而降低医源性神经损伤的风险[49-51]。②希望通过神经外科减压手术改善脊髓牵张, 降低后期矫形风险。但神经外科减压手术本身也存在潜在手术风险, 且分期手术增加患者的痛苦和经济负担[52-53]。近年来, 一些外科医师尝试用IS的治疗策略对合并ChiariⅠ型畸形和脊髓空洞症的脊柱侧凸患者治疗[21, 36, 54], 结果显示, 对于合并ChiariⅠ型畸形和/或脊髓空洞症的脊柱侧凸患者, 冠状面主弯矫形率为59% ~ 71%。Sha等[36]报道脊髓空洞症相关脊柱侧凸组与AIS组在基于椎弓根螺钉内固定的脊柱矫形融合术后主胸弯的矫形率相似(68% vs. 71%)。Li等[21]报道, 严重僵硬性脊髓空洞症相关性脊柱侧凸和严重僵硬性IS患者在基于椎弓根螺钉的后路脊柱矫形融合术后可获得相似的矫形效果。上述研究纳入了部分已接受神经外科干预的合并ChiariⅠ型畸形和/或脊髓空洞症的脊柱侧凸患者, 因此, 脊柱侧凸的矫形结果可能会受到枕骨大孔减压术(FMD)或脊髓空洞分流术的影响, 并不能真实地反映该类患者后路脊柱矫形融合术后的矫形效果。本研究中的研究组患者均在未行神经外科减压手术的情况下直接行一期后路脊柱矫形融合术, 末次随访时, 2组的冠状面和矢状面矫形效果均无差异, 证实ChiariⅠ型畸形和脊髓空洞症的存在并不影响矫形术的疗效。

Ferguson等[55]提出, 合并脊髓空洞的脊柱侧凸患者若具备类似于IS的冠状面特征, 则80%伴有后凸畸形, 同时发现这类患者若初诊为IS并行脊柱矫形融合术治疗, 随访时主弯角度丢失 > 10°很常见。Bradley等[52]和Farley等[56]也报道了类似结果。而本研究中, 2组冠状面矫形丢失率差异无统计学意义, 提示并未因ChiariⅠ型畸形和脊髓空洞症的存在使矫形丢失率增加。本研究与上述报道结果不同的主要原因考虑为本研究纳入的所有患者均使用椎弓根螺钉内固定, 而上述研究使用椎板挂钩或其他传统内固定系统。椎弓根螺钉可提供三柱矫形和内固定, 具有更长的力臂, 可更好地控制端椎, 故椎弓根螺钉内固定可获得更高的矫形率, 并更好地维持矫形率[30, 57]。Wang等[58]采用椎弓根螺钉内固定系统治疗合并脊髓空洞症的脊柱侧凸患者21例, 结果发现, 冠状面矫形平均丢失3°。本研究中, 研究组与IS组冠状面矫形丢失角度分别为3.4°±3.1°和2.9°±1.2°, 与Wang等[58]的报道相似。本研究结果还显示, 术后2周和末次随访时2组在冠状面平衡、SVA、TK、LL、矢状面矫形丢失率、DAR方面差异均无统计学意义;且手术时长、预估出血量、固定融合节段数、螺钉密度等手术情况差异亦无统计学意义;表明尽管2组患者术前脊髓状态存在差异, 但在基于椎弓根螺钉内固定系统的一期后路脊柱矫形融合术中可获得相似的矫形效果和矫形维持效果。

本研究局限性: ①为回顾性研究;②X线片测量存在固有误差;③纳入样本量有限, 对结果的可靠性有一定影响。综上所述, 尽管术前脊髓状态存在差异, 但在年龄、性别、主弯位置、侧凸数量、冠状面影像学参数相匹配的情况下, 合并ChiariⅠ型畸形和脊髓空洞症的脊柱侧凸患者与IS患者具有相似的矢状面影像学参数和主弯柔韧性, 采用基于椎弓根螺钉内固定系统的一期后路脊柱矫形融合术治疗可获得相似的矫形效果。

| [1] |

Geissele AE, Ogilvie JW, Cohen M, et al. Thoracoplasty for the treatment of rib prominence in thoracic scoliosis[J]. Spine(Phila Pa 1976), 1994, 19(14): 1636-1642. |

| [2] |

谢丁丁, 朱泽章, 邱勇, 等. 青少年伴/不伴Arnold-Chiari畸形的脊髓空洞的影像学特征比较[J]. 脊柱外科杂志, 2015, 13(5): 303-306. DOI:10.3969/j.issn.1672-2957.2015.05.011 |

| [3] |

Meadows J, Kraut M, Guarnieri M, et al. Asymptomatic Chiari type Ⅰ malformations identified on magnetic resonance imaging[J]. J Neurosurg, 2000, 92(6): 920-926. DOI:10.3171/jns.2000.92.6.0920 |

| [4] |

张鹏, 郑红绪, 张少军, 等. 应用磁共振相衬技术对Chiari Ⅰ型畸形合并脊髓空洞症的脑脊液动力学研究[J]. 蚌埠医学院学报, 2021, 46(5): 602-605. |

| [5] |

Zhang Y, Wang YS, Xie JM, et al. Cervical abnormalities in severe spinal deformity: a 10-year MRI review[J]. Orthop Surg, 2020, 12(3): 761-769. DOI:10.1111/os.12673 |

| [6] |

Tubbs RS, Beckman J, Naftel RP, et al. Institutional experience with 500 cases of surgically treated pediatric Chiari malformation type Ⅰ[J]. J Neurosurg Pediatr, 2011, 7(3): 248-256. DOI:10.3171/2010.12.PEDS10379 |

| [7] |

Zhang Y, Xie J, Wang Y, et al. Intraspinal neural axis abnormalities in severe spinal deformity: a 10-year MRI review[J]. Eur Spine J, 2019, 28(2): 421-425. DOI:10.1007/s00586-018-5522-3 |

| [8] |

Kontio K, Davidson D, Letts M. Management of scoliosis and syringomyelia in children[J]. J Pediatr Orthop, 2002, 22(6): 771-779. |

| [9] |

朱泽章, 邱勇. 脊髓空洞与脊柱侧凸[J]. 脊柱外科杂志, 2004, 2(5): 299-301, 306. DOI:10.3969/j.issn.1672-2957.2004.05.013 |

| [10] |

Attenello FJ, McGirt MJ, Atiba A, et al. Suboccipital decompression for Chiari malformation-associated scoliosis: risk factors and time course of deformity progression[J]. J Neurosurg Pediatr, 2008, 1(6): 456-460. DOI:10.3171/PED/2008/1/6/456 |

| [11] |

Sadler B, Kuensting T, Strahle J, et al. Prevalence and impact of underlying diagnosis and comorbidities on Chiari 1 malformation[J]. Pediatr Neurol, 2020, 106: 32-37. DOI:10.1016/j.pediatrneurol.2019.12.005 |

| [12] |

Strahle J, Muraszko KM, Kapurch J, et al. Chiari malformation typeⅠ and syrinx in children undergoing magnetic resonance imaging[J]. J Neurosurg Pediatr, 2011, 8(2): 205-213. DOI:10.3171/2011.5.PEDS1121 |

| [13] |

Noureldine MHA, Shimony N, Jallo GI, et al. Scoliosis in patients with Chiari malformation typeⅠ[J]. Childs Nerv Syst, 2019, 35(10): 1853-1862. DOI:10.1007/s00381-019-04309-7 |

| [14] |

Eule JM, Erickson MA, O'Brien MF, et al. Chiari Ⅰ malformation associated with syringomyelia and scoliosis: a twenty-year review of surgical and nonsurgical treatment in a pediatric population[J]. Spine(Phila Pa 1976), 2002, 27(13): 1451-1455. DOI:10.1097/00007632-200207010-00015 |

| [15] |

Strahle J, Smith BW, Martinez M, et al. The association between Chiari malformation typeⅠ, spinal syrinx, and scoliosis[J]. J Neurosurg Pediatr, 2015, 15(6): 607-611. DOI:10.3171/2014.11.PEDS14135 |

| [16] |

陈勃先, 杨华, 孙红, 等. 特发性脊柱侧凸后路手术的研究进展[J]. 中国医学创新, 2020, 17(12): 169-172. DOI:10.3969/j.issn.1674-4985.2020.12.042 |

| [17] |

Suk SI, Lee CK, Min HJ, et al. Comparison of Cotrel-Dubousset pedicle screws and hooks in the treatment of idiopathic scoliosis[J]. Int Orthop, 1994, 18(6): 341-346. |

| [18] |

Shi B, Qiu J, Xu L, et al. Somatosensory and motor evoked potentials during correction surgery of scoliosis in neurologically asymptomatic Chiari malformation-associated scoliosis: a comparison with idiopathic scoliosis[J]. Clin Neurol Neurosurg, 2020, 191: 105689. DOI:10.1016/j.clineuro.2020.105689 |

| [19] |

Scaramuzzo L, Giudici F, Archetti M, et al. Clinical relevance of preoperative MRI in adolescent idiopathic scoliosis: is hydromyelia a predictive factor of intraoperative electrophysiological monitoring alterations?[J]. Clin Spine Surg, 2019, 32(4): E183-E187. DOI:10.1097/BSD.0000000000000820 |

| [20] |

Strahle J, Muraszko KM, Garton HJ, et al. Syrinx location and size according to etiology: identification of Chiari-associated syrinx[J]. J Neurosurg Pediatr, 2015, 16(1): 21-29. DOI:10.3171/2014.12.PEDS14463 |

| [21] |

Li Z, Lei F, Xiu P, et al. Surgical treatment for severe and rigid scoliosis: a case-matched study between idiopathic scoliosis and syringomyelia-associated scoliosis[J]. Spine J, 2019, 19(1): 87-94. DOI:10.1016/j.spinee.2018.05.027 |

| [22] |

Langridge B, Phillips E, Choi D. Chiari malformation type 1:asystematic review of natural history and conservative management[J]. World Neurosurg, 2017, 104: 213-219. DOI:10.1016/j.wneu.2017.04.082 |

| [23] |

American Spinal Injury Association. Standards for neurological classification of spinal injury patients[M]. Chicago: American Spinal Injury Association, 1992.

|

| [24] |

解京明, 王迎松, 张颖, 等. 经后路全椎体切除矫正僵硬性脊柱后凸或侧后凸的初期临床报道[J]. 脊柱外科杂志, 2008, 6(1): 1-4. DOI:10.3969/j.issn.1672-2957.2008.01.001 |

| [25] |

解京明, 徐松, 王迎松, 等. 后路椎体间微粒骨打压植骨融合[J]. 临床骨科杂志, 2006, 9(1): 13-15. |

| [26] |

Lin Y, Shen J, Chen L, et al. Cardiopulmonary function in patients with congenital scoliosis: an observational study[J]. J Bone Joint Surg Am, 2019, 101(12): 1109-1118. DOI:10.2106/JBJS.18.00935 |

| [27] |

McDowell MM, Tempel ZJ, Gandhoke GS, et al. Evolution of sagittal imbalance following corrective surgery for sagittal plane deformity[J]. Neurosurgery, 2017, 81(8): 129-134. |

| [28] |

Feng F, Shen J, Zhang J, et al. Characteristics and clinical relevance of the osseous spur in patients with congenital scoliosis and split spinal cord malformation[J]. J Bone Joint Surg Am, 2016, 98(24): 2096-2102. DOI:10.2106/JBJS.16.00414 |

| [29] |

Glattes RC, Bridwell KH, Lenke LG, et al. Proximal junctional kyphosis in adult spinal deformity following long instrumented posterior spinal fusion: incidence, outcomes, and risk factor analysis[J]. Spine(Phila Pa1976), 2005, 30(14): 1643-1649. DOI:10.1097/01.brs.0000169451.76359.49 |

| [30] |

Dobbs MB, Lenke LG, Kim YJ, et al. Selective posterior thoracic fusions for adolescent idiopathic scoliosis: comparison of hooks versus pedicle screws[J]. Spine(Phila Pa 1976), 2006, 31(20): 2400-2404. DOI:10.1097/01.brs.0000240212.31241.8e |

| [31] |

Legaye J, Duval-Beaupère G. Sagittal plane alignment of the spine and gravity: a radiological and clinical evaluation[J]. Acta Orthop Belg, 2005, 71(2): 213-220. |

| [32] |

Shen J, Tan H, Chen C, et al. Comparison of radiological features and clinical characteristics in scoliosis patients with Chiari Ⅰ malformation and idiopathic syringomyelia: a matched study[J]. Spine(Phila Pa1976), 2019, 44(23): 1653-1660. DOI:10.1097/BRS.0000000000003140 |

| [33] |

Tan H, Lin Y, Rong T, et al. Surgical scoliosis correction in Chiari-Ⅰ malformation with syringomyelia versus idiopathic syringomyelia[J]. J Bone Joint Surg Am, 2020, 102(16): 1405-1415. DOI:10.2106/JBJS.20.00058 |

| [34] |

Marks M, Petcharaporn M, Betz RR, et al. Outcomes of surgical treatment in male versus female adolescent idiopathic scoliosis patients[J]. Spine(Phila Pa1976), 2007, 32(5): 544-549. DOI:10.1097/01.brs.0000256908.51822.6e |

| [35] |

Lewis NDH, Keshen SGN, Lenke LG, et al. The deformity angular ratio: does it correlate with high-risk cases for potential spinal cord monitoring alerts in pediatric 3-column thoracic spinal deformity corrective surgery?[J]. Spine(Phila Pa1976), 2015, 40(15): E879-E885. DOI:10.1097/BRS.0000000000000984 |

| [36] |

Sha S, Qiu Y, Sun W, et al. Does surgical correction of right thoracic scoliosis in syringomyelia produce outcomes similar to those in adolescent idiopathic scoliosis?[J]. J Bone Joint Surg Am, 2016, 98(4): 295-302. DOI:10.2106/JBJS.O.00428 |

| [37] |

张宏其, 陈凌强, 郭超峰, 等. 无神经症状的脊柱侧凸伴脊髓空洞症患者应否外科处理脊髓空洞的临床研究[J]. 中国矫形外科杂志, 2008(13): 961-965. |

| [38] |

Milhorat TH, Nishikawa M, Kula RW, et al. Mechanisms of cerebellar tonsil herniation in patients with Chiari malformations as guide to clinical management[J]. Acta Neurochir(Wien), 2010, 152(7): 1117-1127. DOI:10.1007/s00701-010-0636-3 |

| [39] |

Nishikawa M, Sakamoto H, Hakuba A, et al. Pathogenesis of Chiari malformation: a morphometric study of the posterior cranial fossa[J]. J Neurosurg, 1997, 86(1): 40-47. DOI:10.3171/jns.1997.86.1.0040 |

| [40] |

Honey CM, Martin KW, Heran MKS. Syringomyelia fluid dynamics and cord motion revealed by serendipitous null point artifacts during cine MRI[J]. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol, 2017, 38(9): 1845-1847. DOI:10.3174/ajnr.A5328 |

| [41] |

Oldfield EH. Pathogenesis of Chiari Ⅰ - pathophysiology of syringomyelia: implications for therapy: a summary of 3 decades of clinical research[J]. Neurosurgery, 2017, 64(CN_suppl_1): 66-77. DOI:10.1093/neuros/nyx377 |

| [42] |

Gardner WJ, Angel J. The mechanism of syringomyelia and its surgical correction[J]. Clin Neurosurg, 1958, 6: 131-140. |

| [43] |

Williams B. The distending force in the production of communicating syringomyelia[J]. Lancet, 1969, 2(7622): 696. |

| [44] |

Royo-Salvador MB, Solé-Llenas J, Doménech JM, et al. Results of the section of the filum terminale in 20 patients with syringomyelia, scoliosis and Chiari malformation[J]. Acta Neurochir(Wien), 2005, 147(5): 515-523. |

| [45] |

Levine DN. The pathogenesis of syringomyelia associated with lesions at the foramen magnum: a critical review of existing theories and proposal of a new hypothesis[J]. J Neurol Sci, 2004, 220(1-2): 3-21. |

| [46] |

Diab M, Landman Z, Lubicky J, et al. Use and outcome of MRI in the surgical treatment of adolescent idiopathic scoliosis[J]. Spine(Phila Pa 1976), 2011, 36(8): 667-671. |

| [47] |

Lenke LG, Betz RR, Harms J, et al. Adolescent idiopathic scoliosis: a new classification to determine extent of spinal arthrodesis[J]. J Bone Joint Surg Am, 2001, 83(8): 1169-1181. |

| [48] |

Rose PS, Lenke LG. Classification of operative adolescent idiopathic scoliosis: treatment guidelines[J]. Orthop Clin North Am, 2007, 38(4): 521-529. |

| [49] |

Lu VM, Phan K, Crowley SP, et al. The addition of duraplasty to posterior fossa decompression in the surgical treatment of pediatric Chiari malformation typeⅠ: a systematic review and meta-analysis of surgical and performance outcomes[J]. J Neurosurg Pediatr, 2017, 20(5): 439-449. |

| [50] |

王效宝, 胡涛, 闫晓鹏, 等. Chiari畸形诊断和治疗新进展[J]. 山西医药杂志, 2015, 44(11): 1263-1266. |

| [51] |

Strahle JM, Taiwo R, Averill C, et al. Radiological and clinical associations with scoliosis outcomes after posterior fossa decompression in patients with Chiari malformation and syrinx from the Park-Reeves Syringomyelia Research Consortium[J]. J Neurosurg Pediatr, 2020, 26(1): 53-59. |

| [52] |

Bradley LJ, Ratahi ED, Crawford HA, et al. The outcomes of scoliosis surgery in patients with syringomyelia[J]. Spine(Phila Pa 1976), 2007, 32(21): 2327-2333. |

| [53] |

Soleman J, Roth J, Bartoli A, et al. Syringo-subarachnoid shunt for the treatment of persistent syringomyelia following decompression for Chiari typeⅠ malformation: surgical results[J]. World Neurosurg, 2017, 108: 836-843. |

| [54] |

Feng F, Shen H, Chen X, et al. Selective thoracolumbar/lumbar fusion for syringomyelia-associated scoliosis: a case-control study with Lenke 5C adolescent idiopathic scoliosis[J]. BMC Musculoskelet Disord, 2020, 21(1): 749. |

| [55] |

Ferguson RL, DeVine J, Stasikelis P, et al. Outcomes in surgical treatment of "idiopathic-like" scoliosis associated with syringomyelia[J]. J Spinal Disord Tech, 2002, 15(4): 301-306. |

| [56] |

Farley FA, Song KM, Birch JG, et al. Syringomyelia and scoliosis in children[J]. J Pediatr Orthop, 1995, 15(2): 187-192. |

| [57] |

Liljenqvist U, Hackenberg L, Link T, et al. Pullout strength of pedicle screws versus pedicle and laminar hooks in the thoracic spine[J]. Acta Orthop Belg, 2001, 67(2): 157-163. |

| [58] |

Wang SW, Samdani AF, Stanton P, et al. Impact of pedicle screw fixation on loss of deformity correction in patients with adolescent idiopathic scoliosis[J]. J Pediatr Orthop, 2013, 33(4): 377-382. |

2024, Vol.22

2024, Vol.22  Issue(2): 73-80, 86

Issue(2): 73-80, 86